The corporate playing field

The corporate playing field

LABELS such as "Made in Japan", "Made in Germany, "Made in USA" are losing their meaning. Modern communications technology, collapsing international trade barriers and increasing competition are expanding the global economy. As a result, the service and industry sectors are being transformed and integrated across the world in an unprecedented manner, according to World Investment Report 1993, a UN publication. Today, the antecedents of products and services available in the global marketplace are getting obscured.

Forced to streamline operations to maintain their competitive advantage in a world hit by severe economic recession, transnational corporations (TNCs), which control most of the world's production of goods and services, are reorienting their strategies at two levels: They are restructuring relationships with affiliates and are increasingly entering into alliances with competitors to maintain their market share.

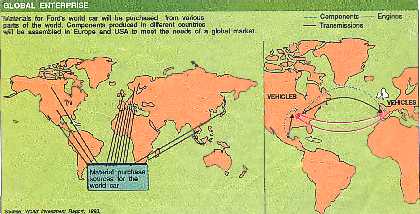

For example, automobile giants Ford, Nissan, Toyota, General Motors and Mazda have established networks across nations to integrate research and development, component manufacture and inventory systems. At the same time, Ford is planning to produce a "world car" that is assembled and sold globally (See box).

In the highly competitive semiconductor industry, US giant IBM, Siemens of Germany and Toshiba of Japan have formed an alliance to develop a new 256-megabyte computer chip by the end of the century. This alliance, they believe, will enable them to share the huge $1 billion costs involved in the design and fabrication of the chip and the risks associated with it.

Easy communication Behind the globalisation of production and services is cheap and fast communication through such phenomenal advances in informatics and telecommunications as faxes, modems, computer networks and video-conferencing. Higher information processing and communicating capacities make it increasingly possible for production to be integrated in various parts of the world. Falling prices of information technologies have decentralised their access and use within corporations, paving the way for the spread of flexible production technologies and new management and research and development practices.

Computer networks within and between organisations are redefining hierarchical structures, revolutionising the work environment and creating horizontal and vertical linkages and flows of information. Information technologies are also crucial in managing links across time zones and countries and in responding rapidly to changing conditions in a competitive environment.

Estimates are that up to one-third of the world output is potentially subject to these integrated production strategies. As much as a third of US output and a quarter of Japanese sales are potentially part of an internationally integrated production and experts point out that the share of integrated production in other developed countries like Germany and the UK may be higher.

Changes within Gone are the days when TNCs were happy at making inroads into national markets by setting up partly or wholly owned affiliates in other countries to whom they supplied technology. Now, the relationship between parent TNCs and their operating in foreign markets has begun to change. Instead of separately meeting the needs of national and regional markets, products are being manufactured for the global market, which has become the new playing field.

Integrated international production means that an affiliate operating in any location potentially performs functions for the TNC as a whole or in close interaction with other affiliates on the basis of a sophisticated internal division of labour. Various affiliates across the world now function as the heart or liver of an organisation.

The integration of production is especially noticeable in those service functions that have become tradeable over computer communication networks. Not only have production processes spilt up to be undertaken in different regions, but firms are also beginning to operate continuously by taking advantage of shifting tasks to different time zones. As yet, few corporations have integrated production to this extent, but they are increasingly looking to exploit the locational advantages that other parts of the world offer.

It's better abroad

The availability of skilled labour and professionals, cheap transportation and other physical infrastructure and services in host countries has enabled transnational corporations to go wherever they can perform most efficiently and economically.

Large retail chains like the UK-based Marks and Spencer rely heavily on goods produced in developing countries, where labour costs are lower. Nike, the US sports accessories manufacturer, subcontracts the manufacture of clothing and sportswear to 40 locations, mostly in south and southeast Asia. Designs are done by the parent firm and relayed by satellite to the manufacturing facility in, say, Taiwan. Prototypes are then constructed and modified and final plans are faxed to production subcontractors throughout the region, where Nike employees ensure quality control. The output is marketed by the parent company worldwide.

In the services sector, too, corporations use foreign affiliates or subcontractors to process data or develop software. India, with thousands of computer professionals, is increasingly attracting numerous computer and software firms from abroad. Texas Instruments, Motorola, Hewlett-Packard, Apple, Sun Microsystems and Intel have all set up operations in India. Dell Computer Corp plans to establish a plant to manufacture computer motherboards for export and IBM has formed a joint venture with the Tatas.

Indian companies are also winning orders to supply software to foreign clients. Infosys, an Indian software group, provides Holiday Inn with hotel reservation software connected directly with the computer centre of the Holiday Inn Hotel chain in the US. Experts in India are also developing software for companies like Swissair, which has relocated its global accounting operations to Bombay (See box).

To take advantage of scientific and technical skills available abroad, a growing number of TNCs are locating a small but rising portion of their R&D outside their home countries, closer to factories and markets. The new information technologies are also having a profound impact on R&D, especially in such industries as aerospace, automobiles, electronics and biotechnology.

Finance management

Liquidity management and other aspects of the finance function are being located where they best meet the needs of a corporation. The US affiliate of Siemens transmits daily financial information to its headquarters, where the company's entire financial management occurs.

Organisations like Unilever and Thomson are separating manufacturing and marketing functions and developing global marketing strategies. But these technologies are also being exploited by firms operating in special niche markets, without losses due to higher costs. Companies like the Italian fashion clothier Benetton and the US-based jeans manufacturer Levi Strauss are increasingly using the new information technology to match production more closely to demand in the countries in which they operate.

So far, mainly developed countries are suited to participate in integrated international production. But increasingly, experts contend, newly industrialised countries and larger developing countries are latching on to the emerging system by attracting foreign investments because they offer labour skills, favourable policy environments, efficient transportation and communication networks and often access to a large and growing regional economy. More work is being parcelled out to distant locations with capable labour forces.

Countries like Singapore are bending over backwards to attract foreign investment. Being developed as a world class transportation hub, for passenger as well as air and sea cargo in southeast Asia, the government there has consistently invested heavily in transportational infrastructure. Located in a time zone that overlaps Asian and European financial markets, several fiscal incentives have been introduced to encourage corporations to locate regional or global finance headquarters in Singapore. Attempts are also being made to attract the R&D headquarters of TNCs, especially in agro-technology, biotechnology, robotics and automation.

But the emerging integrated international production system in this fast-moving world, which is shrinking at a phenomenal rate, has left many developing countries untouched. And, the indications are that countries, especially those in parts of Africa and Latin America, risk being marginalised further because they do not offer locational advantages required by globally integrated firms such as skilled labour forces, open trading and investment climate, developed communication and transport infrastructure and networks of local suppliers. In the new world order, countries like India have little option but to join in.