Future tense

Future tense

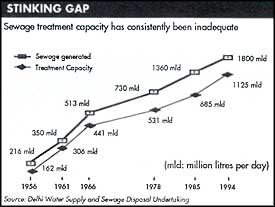

THIS is not a load of what you think it is. By the year 2001, the volume of sewage generated by Delhi is likely to top a mountainous 3,200 mId.

The only way to flush it or purify it is with more water. And no one knows where that is going to come from, apart from one of the priorities of the city's Eighth Five Year Plan, which envisages making investments in future projects. Whatever that may mean.

There has already been roundhouse criticism of the official claim that dams like Tehri, Renuka and Kishau (see box Thrice dammed) will ever be able to meet the water requirements of the city. Even if they could, Delhi's financial share in these dams - none of which can be completed before 1998 in any case - will vacuum out its resources.

An anticipated pockets-turned-out situation is why chief minister Khurana now seems to be insisting that the city be provided with water from the sluggish Yamuna through a new accord: "This water," he says, will be much cheaper than water from Tehri. "

But what no administrator is able to explain is: if the supply does reach its projected volume, how is the city going to meet its treatment, supply and disposal costs in the future? Three voices:

"There are no soft options. It is clear that the era of cheap water is over," says Ramaswamy Iyer, former Union water resources secretary and an expert on water- related issues. The engineer-in -chief of DWSSDU, S Prakash, insists that cost recovery must play an emphatic role in fixing water supply charges. Pricing as a means of demand management is a must, says Paul Appasamy of the Madras Institute of Development Studies. In Delhi's case, it appears to be particularly important because cheap water, more than anything else, has prevented every major initiative in both disciplined use of water and its recycling.

Delhi is a prime example of absurd hospitality. In many water scarce cities in the developed world, water is used as many as 25 times before it is finally disposed of but recycling of water even for horticultural and industrial purposes is treated with a wrinkled nose here. Says Arun Jain, assistant chief engineer of Hotel Hyatt Regency in Delhi, "How can you use recycled water in a premium hotel? The guests will be put off" (see box Luxurious guzzling ... ).

Even the 30 mid of horticultural demand within Delhi is supplied with fresh Water brought all the way from the Bhakra canal. Similarly, few industries, if any, recycle their water because "it makes better business sense to buy water from the municipal agencies than to invest in recycling it," says Appasamy. He argues that while a remunerative pricing of water is important to discipline consumption, the denial of access to fresh water is most likely to bring big consumers like industries and commercial establishments in line, "The Madras experience shows that the business community will opt for recycling if water is not available to it at all," he says.

Technological innovations can help propel financial savings. Take flushing cisterns: while manufacturers like Hindustan Sanitaryware have developed cisterns that use as little as 3.5 litres, they confess to facing problems in marketing them because the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) has not yet chalked out a system of standardisation of flushes in the water-saving category. "Without BIS certification, nobody wants to install a new cistern, especially if all the old ones carry the stamp," says a company official.

And these little flushes cost more for their size. Manufacturers defend themselves saying that precision technology and superior material cost that much more; but not many consumers, nevertheless, want to pay more money when they do not, under threat of law, have to. As to augmenting water resources at economical rates, the only foolproof plan that the government seems to have is importing water over great, foolish distances. Advocates of water conservation like Anupam Mishra of the Gandhi Peace Foundation, however, pinpoint an area of tremendous scope: the traditional water reservoirs of Delhi a large number of which have either been reclaimed or are severely degraded.

According to Mishra, during the early decades of this century, Delhi had as many as 360 ponds and water reservoirs through which the city met most of its water needs. Even today, he says, they -can be tapped to reduce the extraction of groundwater through tubewells.

In the final analysis, a gritty And enforceable legislative framework for conservation-oriented use of water is missing. Even a tentative draft bill circulated over a year ago by the Union water resources ministry has failed to move the city's administrators. There are no restrictions on punching a hole in ground and bleeding aquifers dry. Water- scarce cities like Madras, meanwhile, have banned the individual exploitation of groundwater.

While justifiable fears lurk around about the misuse, corruption and inequities inherent in legislative measures, Appasamy admits that he would endorse them for lack of a better option. Within the government itself, surprisingly, takers for this option are few and full of trepidation.

The final say is CGWB's S K Sharma. "How can you stop people from getting water?" he asks. "People have to be given water."

The questions are: how much? And at whose cost?