The best guide

The best guide

in a society that is fast depending on compelling scientific evidence, often explanations as 'gut feeling' or intuition for taking a particular decision are laughed at. But scientific evidence has just surfaced to show that intuition indeed plays a crucial role in helping people make sensible decisions and clues to how 'gut feelings' work in the brain (Science, Vol 275, No 5304).

Neuroscientists Antoine Bechara, Hanna Damasio, Daniel Tranel and Antonio Damasio of the University of Iowa, College of Medicine in Iowa City set out to investigate the role of intuition in the decision-making process by studying a group of brain-damaged individuals who appeared unable to make 'good decisions'. Some 'bad' decisions include drifting in and out of marriages, squandering money or offending colleagues inadvertently.The researchers found that the patients lacked intuition, which many psychologists think may be based on memories of past emotions and experience.

This study also dispels the lingering notion that emotions and other feelings are somehow unimportant in decision-making. Neuroscientists have long known that the brain stores, processes and retrieves a wealth of information at a non-conscious level than the conscious mind uses. But they do not know much about which part of the brain is involved in the process and how precisely it works.

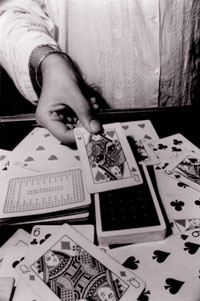

In the present investigation, the researchers examined 10 normal people and six people who had suffered damage to a part of the brain above the eyes called the ventro-medial sector of the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in decision making. Such brain-damaged people have normal intelligence and memory, but tend to display little emotion and have trouble in making sound decisions. The researchers gave each of the 16 participants us $2000 in play money, presented them with four decks of cards and told them they could draw cards from any deck. They would lose or win money depending upon the cards they turned up. What is not known to the participants was that two decks were stacked to make players lose overall if they picked from these decks, even though these decks would initially yield profits. The other decks paid off less at the beginning but ultimately gave overall benefit.

All the subjects had sensors attached to their palms that detected changes in the electrical conductance of the skin to detect signs for anxiety, like sweating or palpitation, whether they were conscious or not. After twenty turns to each participant, the researchers stopped the game and there after every 10 turns they were asked questions to determine whether they were aware of the best strategy to win money. As expected, normal subjects became quite anxious after losing and were hesitant to pick cards from the losing decks. And they started avoiding cards from these decks well before they consciously became aware that they were losers, which is what we call intuition.

So by about card 50, all normal participants began to get a 'hunch' that decks a and b were riskier and all generated anticipatory sweating whenever they pondered a choice from deck a or b. By their 80th turn, seven of the 10 normal participants consciously knew how to win by avoiding the losing decks. Remarkably, the other three normal volunteers who did not reach the other decks still made advantageous choices demonstrating that intuitive knowledge was influencing their behaviour.

In sharp contrast, the brain-damaged people never showed signs of anxiety, never expressed a hunch that some decks were losing ones and continued to pick cards from them, demonstrating that they had been unable to gain access to intuitions. In fact, just as remarkably, the three patients with prefrontal damage who reached the conceptual period and correctly described which were the bad and good decks chose disadvantageously. They, therefore, failed to act according to correct conceptual knowledge.

Based on the data, the researchers concluded that decision-making in normal people requires two parallel but interacting chain of events. One involves activating a brain circuit that includes the ventro-medial frontal cortices, which stores knowledge about a person's emotional experiences -- his or her intuition.

In normal people, the researchers concluded, that part of the brain sends signals to other parts of the brain, which recall the overall facts of a situation, including various options and possible outcomes, and use the unconscious knowledge - intuition - to make the right decision.