Everything you want to know about biodiversity, except...

Everything you want to know about biodiversity, except...

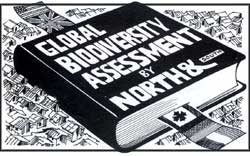

IN LESS than a year from now, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) plans to put out an omnibus book on biodiversity. But Indian experts are not too sure that all "issues and views of the South" will find place in the book on Global Biodiversity Assessment (GBA).

UNEP's ambitious task is to bring out an "independent, peer-reviewed, scientific analysis of the issues, theories, and views on global aspects of biodiversity." A team of editors, authors and experts from various countries has been working on the draft since June 1992, when the idea of GBA was mooted. Several workshops are being held to identify gaps in the draft text and remove them.

One workshop was held in Bangalore in July. It reviewed the draft text of 2 chapters dealing with the human impact on biodiversity and measures to conserve biodiversity and the sustainable use of its components. At this workshop, Kenton Miller, programme director of GBA from the New York-based Biological Resources Institute, said, "GBA will surely represent varying perceptions on biodiversity management from different parts of the globe."

But A K Ghosh, director of the Zoological Survey of India, said the draft "was heavily biased towards the West, with few illustrative cases from our part of the world. We need to be careful about this because conservation priorities have been developed largely outside our national landscape."

Major changes were suggested to make the document truly "representative". Ashish Kothari of Kalpavriksh, a Delhi-based NGO, emphasised that the Northern approach to protected area management should be revised to integrate the needs of the people living there. He added that the whole issue of access and property rights in such areas should be revised in the light of the Southern experience.

Some participants found the draft biased and silent on certain subjects. "Pressing issues like the North's inequitable consumption pattern, which has grave implications for biodiversity conservation, were left out of the purview of the draft," pointed out Kothari.

However, Jeffrey McNeely of the World Conservation Union (IUCN), one of the project coordinators, argued that the purpose of the workshop was precisely this: to invite opinion and suggestions on shortcomings and gaps in the draft.

Several participants were surprised at the absence of issues relating to the North-South debate on transfer of technology, access to genetic resources and intellectual property rights (IPR) to indigenous knowledge. For instance, even after the Convention on Biodiversity and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade established sovereign rights and strengthened proprietary rights, respectively, over biodiversity, GBA overlooks such rights.

Speculative debate

Said Miller, "The debate on IPR is still very speculative and nothing concrete is available on the mechanism for its protection." The coordinators finally agreed to discuss the issue in the section on biotechnology, but Indian participants want it to be included in the section on indigenous knowledge and to state clearly the legal mechanisms for its protection.

The hesitation of the project chiefs in getting into the contentious issues stems partially from doubts expressed by some countries that GBA might try to prescribe solutions and interfere in their internal matters. But Miller avers, "GBA is not a political document. Nor is it in the business of prescribing solutions to problems. We want scientific analysis of issues which will act as useful references."

Therefore, when S C Dey, additional inspector general of forests from the environment ministry, toed the official line and pleaded against giving too many concessions to the local people because "people overexploit under the garb of sustainability," McNeely dissuaded him, saying, "We are here to find out how much we know about use of biodiversity, not to prescribe its use."