Was India forced to reject World Bank aid?

Was India forced to reject World Bank aid?

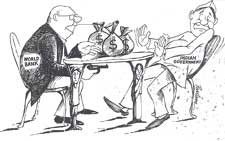

DELIVERANCE for the World Bank (WB) could be damnation for the Indian government. When India surprisingly announced on March 30 that it would reject WB aid of Rs 500 crore for the Rs 13,000-crore Sardar Sarovar project, some observers commented the WB had arm-twisted India into refusing its funds for the project to save WB's skin.

Foreign lobbyists unequivocally condemn the WB for pressuring India to refuse bank funds. Says Patricia Adams, executive director of Probe International, a Canadian lobby that's opposed to the dam, "In an effort to save its own hide, the bank asked India to ask the bank to withdraw from the project...The bank weasled its way out of the project...because it started to harm its ability to replenish its finances."

Charles Secrett, director of the London-based Friends of the Earth, also blames the WB on the issue, saying, "The project exemplified the World Bank's problems of unaccountability, arrogance and secrecy, and the whole direction of development it is trying to force on the world."

In New Delhi, a senior official of the Union ministry of water resources disclosed the government had a fair inkling of the event. And, an additional secretary in the same ministry notes, "India had realised that the bank, under pressure from its major donors, would stop funding the Sardar Sarovar project, even if the bank's conditionalities and benchmarks had been met by the March 31 deadline."

In contrast, the Union finance ministry, though reticent about negotiation details, insists WB pressure had nothing to do with its decision to refuse further funding. Finance secretary Montek Singh Ahluwalia told Down To Earth, "We took the decision (to refuse WB funds) because we did not want this issue to be politicised in international fora. There is no question of it being a face-saving measure on our part to pre-empt stoppage of bank funding."

But reports from countries on WB's executive board suggest because Indian authorities would not be able to implement the benchmarks in time, there was considerable pressure to discontinue project funding. Says Micheline Aucoin, a Canadian finance ministry official, "We were under the strong impression that it would take two to three years to bring the project up to standard...given the political crisis in India." Several donor countries -- USA, Germany, Japan, Australia, Canada and the Scandinavian nations -- dissented when the WB's executive directors voted in October 1992 to continue funding the Gujarat project.

Ahluwalia dismisses allegations that India had asked for funding to be terminated because it could not meet the benchmarks in time. But other government officials doubted whether India would have been able to meet the WB's benchmarks deadline of March 31, partly because of the Ayodhya crisis and the subsequent rioting.

Some finance ministry sources attach considerable significance to the impasse at a March 25 meeting on the benchmark issue, which was attended by the chief ministers of the four states involved in the project -- Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan -- the Union ministers of environment, finance and water resources and the Prime Minister. No solution was reached at the meeting on solving problems concerning payments and rehabilitation.

Whatever the finance ministry's views on benchmarks, anti-dam activists doubt whether the conditionalities can be met. Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA) leader Medha Patkar, who spearheaded the anti-dam agitation, told Down To Earth, "The track record of both the Indian government and the bank is deplorable concerning identification of land for rehabilitation and resettlement." She says, "The authorities manipulated them to make it appear as if these had been met, without actually having done much. For example, one of the earlier stipulations was that 2,000 ha of oustee-approved agricultural land had to be acquired in Madhya Pradesh. This was changed to say that 2,000 ha of such land had to be identified."

And lawyer and NBA member Girish Patel, citing police firing in Anjanwara village in Jhabua district of Madhya Pradesh, says, "The poor track record of the authorities extends to human rights as well." The shooting on January 29, in which many were injured, occurred when villagers resisted a team carrying out a survey among displaced people.

Apprehensive of such incidents, anti-dam activists are reviewing their strategies. Though contending that it is easier to fight from within the country, Patkar notes, however, that the agitation is entering a mass-based stage and NBA will seek support from international human rights organisations, which have considerable clout with North governments that provide the funding. The activists are aware that adverse human rights reports could jeopardise such funding.

New strategy

But activists who support the project dismiss Patkar's claim that the agitation was becoming broad-based. Says Sanat Mehta, once chairperson of Sardar Sarovar Narmada Nigam Ltd and now involved in the implementation of the rehabilitation and resettlement package, "The people's movement is very weak in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. With the exception of NBA, there is no organised resistance to the project."

Project supporters feel work on the dam can continue until in about three years it reaches a height of 96 metres. Says vice-chancellor Y K Alagh of Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, "There are adequate resources for rehabilitation and resettlement to go pari passu (simultaneously and equally) with dam construction. I am confident that after this stage is reached in 1995 when the number of families to be resettled increases exponentially, the resources will be found."

In the absence of WB funding, the Gujarat government has considered such options as non-resident Indian bonds worth Rs 500 crore or Narmada bonds to raise Rs 300 crore from the domestic market. But the Centre dismissed the NRI proposal citing restrictions on repatriating foreign exchange and rejected the Narmada bonds proposal because of bond guarantees. The Sardar Sarovar authorities also considered separating the project's power and irrigation components so that private funding could be sought for power and the four states would continue to fund irrigation. A move to transfer the project to the Central sector to make it eligible for Central funding ran into political difficulties.

Union officials, however, are confident that money for the project will be found. Says B N Navalawala, irrigation advisor to the Planning Commission, "The Eighth Plan envisages a total outlay of Rs 22,000 crore on major and medium irrigation projects. This will be more than enough to fund this project without assistance from the World Bank." Navalawala says other states could be solicited for funds to finance the project's power component.

Political views within India on the project differ sharply and even to the extent that a party can have differing stands at the state and national levels.

The Gujarat unit of the BJP, for example, has criticised the government for refusing WB aid, saying the irrigation component would have benefitted party strongholds in the state. But the BJP's central leadership welcomed the aid refusal and BJP supremo Atal Behari Vajpayee says, "At least we can now stand on our own feet."