The East Coast Road to ecological disaster

The East Coast Road to ecological disaster

THE TAMIL Nadu government's plan to construct a 737-km coastal highway from Madras to Kanyakumari has run into rough weather. Work on the 170-km stretch from Madras to Cuddalore came to a stop pending an environmental committee assessment of the impact of the Asian Development Bank-assisted highway project on the coastal ecology.

The decision follows objections from the Union ministry of environment and forests (MEF) that construction had begun without obtaining the requisite environmental clearance under the coastal zone regulations that govern all major development projects. Both the MEF and its minister, Kamal Nath, were under pressure from environmental groups in Madras and Pondicherry, including the Indian National Trust for Art and Culture (INTACH), who assert the ECR will degrade coastal ecology and make the region more vulnerable to cyclones.

These groups met with notable success when a Pondicherry-based architect, Ajit Koujalgi, and some others obtained a stay order from the Madras High Court on December 24, 1992. The court accepted Koujalgi's contention that an environmental impact assessment (EIA) is needed before construction begins.

Ecological damage Environmental protests became vociferous following the INTACT report last November, copies of which were submitted to Kamal Nath as well as Union surface transport minister Jagdish Tytler. The report stated, "One of India's most beautiful, unique coastal ecosystems will be irreparably damaged." Activists say they are particularly alarmed as ECR is part of a plan to eventually link Calcutta with Kanyakumari by a coastal highway. Surface transport officials, on the other hand, dismiss these fears as baseless. The additional director general of roads in India, R P Sikka, said there was "no plan for a coastal highway of the kind environmentalists are talking about. A narrow coastal road exists even now. It is being widened and improved to take more traffic. That's all."

Forests endangered

The INTACT report, publicised in New Delhi by its directors, N D Jayal and Amita Beg, contends that on the Madras-Cuddalore stretch alone, more than 10,000 banyan, tamarind and palmyra trees on both sides of the road will need to be cut down. These trees now act as windbreakers and protect settlements from cyclones. Rich mangroves near the coastal towns of Pichavaram and Muttupet face destroyed and the country's only surviving coastal evergreen forest at Marakkanam and Pudupet would be threatened because the road alignment runs wihtin 100 metres of the forest.

Ground water reserves close to the coast would be seriously damaged. "The coastal highway falls within 6 km of the coastline, where drilling of borewells is explicitly prohibited due to the danger of salinating the soil and groundwater reserves," says the report. "A big highway will inevitably attract industrial and large-scale agricultural development and the pressure to drill borewells will be very high to meet fresh water requirements."

The road embankment will interfere with the tidal flushing of the coastal areas by the Bay of Bengal and this would endanger backwater estuaries and other repositories of sea and shore biodiversity. The report also states that the Point Calimere bird sanctuary and the Talaynayar reserved forest and two important habitats for migratory birds -- Marakkanam Creek and Kaliveli Tank -- are threatened by the ECR.

Beg, expressing concern about the region's "social ecology", argued the road would split a number of villages and affect houses, land-holdings, the community and religious places and expose residents to road accidents and traffic pollution. "Even after this damage," Beg pointed out, "no one could say with certainty that the road itself would survive, because of deposition of sand and the shifting shoreline." This has already led to the shifting further inland of the marine drive from Konark to Puri. And at Mamallapuram and other sites, parts of the road has vanished into the sea.

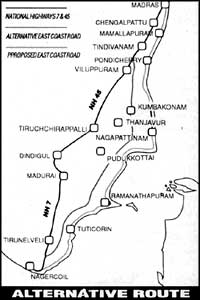

But Koujalgi is at pains to note that they are not protesting the local people's right of access to traffic. Short-distance needs can be adequately met, if existing, narrow coastal roads are improved and heavy-duty and long-distance traffic could use National Highway 45, which runs 10-30 km inland from the coast. The national highway is being widened with World Bank assistance, argues Koujalgi, and it will then be able to accommodate the growing traffic. However, if a new highway was a must, Koujalgi said it should run further inland.

But there are those like Jaya who argue that with the acceleration of economic liberalisation, coastal ecology may break down not only in Tamil Nadu, but all over the country. The only way out, says Jayal, is to develop an integrated land-use plan for coastal areas -- a proposal that has long been languishing with the government.

Whether the East Coast Road will finally take a curve inland is difficult to state now, but with the environmentalists threatening to take to the streets, it is certain there are many more bumps ahead for the controversial highway.