I feel therefore I am

I feel therefore I am

While neuroscientists look for the secret of consciousness in thinking, a psychologist Nicholas Humphrey has put forward the concept that senses or feelings hold the key to the most elusive of the mind's mysteries.

Thinking was considered uniquely human, until the British mathematician Alan Turing's hypothesis that thoughts could be mapped onto symbols, that these symbols could be physical objects and that toying with these objects could be as good as toying with thoughts.

These days the gurus of artificial intelligence take it for granted that consciousness is nothing more than sophisticated information processing--and talk about robots that would be conscious merely by virtue of their ability to manipulate symbolic representations (I process, therefore I am).

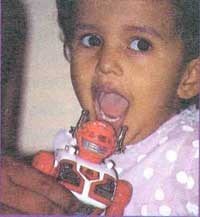

But Humphrey in his widely acclaimed book A History of the Mind, argues that in the kinds of questions people ask about consciousness--are babies conscious? Will I be conscious during the operation? How does my consciousness differ from yours? and so on--the central question is not thinking but feeling. What concerns people is not so much the stream of thoughts running through their heads, as the sense they have of being alive, with pains in their feet, tastes on their tongue, and colours in front of their eyes.

For Humphrey, what matters is the subjective quality of these sensations: the peculiar painfulness of a thorn, the saltiness of an anchovy, the redness of an apple, the effect on us when the stimuli from these external objects meet our bodies and we respond. A person can be conscious without thinking anything. But a person simply cannot be conscious without feeling. I feel, therefore, I am.

But if these are very private sensations, with no public consequences for our behaviour, why did nature permit them to evolve? After all, nature selects only those traits that improve our chances of survival.

Humphrey believes that sensations are both private and have been shaped by selection, though not at the same time. Sensations, for him, began their evolutionary life as bodily reactions. Explains he, "For a primitive organism, the activity of sensing red, for example, would have involved responding to stimulation by red light with a particular sort of wriggle in the area where the stimulation was occurring. Let's call it a 'red wriggle'. Likewise, a green wriggle, blue wriggle, and so on. And the same went on for salty wriggles or ticklish wriggles."

Somewhere along the path of evolution, the wriggles in response to stimuli became less important to survival. "But by then," surmises Humphrey, "the organism had come to rely, for other reasons, on having a mental representation of the stimulation. And so the only way it could tell what was happening at its body surface was by issuing commands for an appropriate wriggle and then letting these commands represent what was happening."

Because there was no longer any point in actually carrying out these commands, they, as it were, could be short circuited. And so the whole sensory activity became closed off from the outside world, in an internal loop within the brain.