Doomed tomb

Doomed tomb

SHAH JAHAN'S dream in marble is at greater risk from pollution today than two decades ago, when protest over damage to the Taj Mahal was at its peak. But even after 20 years, experts are still at odds on how serious is the threat to what is arguably the world's best-known monument.

The original controversy in the 1970s was touched off by the proposal to build a sulphur dioxide-emitting refinery at Mathura, about 40 km away from the Taj Mahal in Agra. Questions were raised in Parliament about the fate of the Taj, besides a spate of newspaper articles, television debates and court cases. The rest of the world joined the debate.

The Texas-based Energy Week advised its readers: "If you want to see the Taj Mahal, better go now!" French President Francois Mitterrand expressed concern that sulphur and nitrogen oxides, which form marble-damaging acids in the presence of moisture, posed a threat to the monument. And, Uniterra, published by the United Nations Environment Programme, warned atmospheric acids would soon make the damage to the Taj visible.

Responding to the pressure, the Central and state governments made their traditional gesture and appointed committees of inquiry. But they also banned air-polluting industries in a 10,400-sq-km area around the Taj, modified the design of the Mathura refinery, relocated foundries to an industrial estate and closed two thermal power plants in Agra city. The last measure had some effect for the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) reported atmospheric sulphur dioxide around the Taj fell 75 per cent between January-March and April-September, in 1981.

Environmentalists who had raised the alarm initially were lulled by these actions. B K Thapar, former director general of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and now secretary of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, admitted he had not visited the Taj in at least five years and was not aware of developments there.

Pollution abounds G Naqshband, managing director of Sita World Travels and an active member of the Indian Heritage Society -- formed in the 1970s to save the Taj -- notes that pressure for action was absent "because we felt the ministry of environment and forests (MEF) has been doing an excellent job". His faith is under challenge now. In recent years, emission restrictions have been widely flouted, new forms of emission have risen rapidly, and there is mounting pressure to establish more industries in the area. Agra's industrialists argue they provide jobs and livelihoods and are not to blame for pollution, but their arguments do not take into account the Taj's unique position in India's heritage; nor do they weigh the enormous revenue the Taj generates.

The growth-rather-than-conservation approach is summed up by Kiran Dhawan, an industrialist and secretary of the Foundry Nagar Association of Agra, who says: "The Taj is not as important as human life."

This approach has resulted in the number of brick kilns in Agra increasing from 16 in 1981 to 227 in 1993 and diesel engine manufacture now at about one lakh a year, compared with virtually none in 1981. Increases of between 25 and 100 per cent are also reported in the number of units engaged in chemical, rubber, engineering and other industrial activities. And, industry representatives concede there are many unregistered air-polluting plants operating in the city.

More and more generators that the UP Pollution Control Board (UPPCB) says are polluting because they release carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides fumes are being used by hotels, industries, banks, offices, shops and even homes. The number of gensets in use is estimated at 20,000-40,000. Comments a local industrialist: "Economics over-ride legality in the use of generators."

Another resident adds, "Is my generator the only cause of pollution? What about the diesel-operated Tempos and Vikrams that produce obnoxious fumes?" Agra commissioner B K Chaturvedi wants top priority to be given for an Agra bypass to reduce vehicle emissions.

Yogendra Kaushal, president of the National Chamber of Industry and Commerce, insists foundries in Agra were unfairly tarred by an expert committee in the 1970s, which branded them a major source of sulphur dioxide. A recent survey by the Process and Product Development Centre (PPDC), Agra, a government-sponsored organisation, lists foundries as only the sixth biggest source of sulphur dioxide in the vicinity of the Taj. The top five are the Mathura refinery, 58 per cent; industries using steam coal, 15 per cent; brick kilns, 13 per cent; domestic, 4 per cent, and vehicles 3 per cent.

Anti-pollution technology is seen as an expensive irritant. Only eight foundries have installed induction-melting furnaces, which use electricity instead of coal. But these cannot be adopted universally, as they are viable only for better-quality castings.

Only two foundries have installed pollution control devices to restrict suspended particulate matter (SPM), which consists of any solid particles in the air that affects the rate of conversion of sulphur dioxide to its trioxide. According to G N Garg, head of the UPPCB office in Agra, control devices tested in the city can reduce spm in stack emissions from 1.8 kg per cubic metre to 250 mg, as against the government-set target for foundries of 150 mg.

A foundry owner, who is also a former president of the Agra Iron Founders Association, contends industry is not making such investments because of uncertainty over how to meet the requirements of the Pollution Control Act: "We can invest," he says, "if UPPCB specifies the technology that will enable the foundries to achieve the standards laid down."

But even if the technology exists and is available, will it be used? According to Kaushal's estimates, "95 per cent of the industry does not have the finances to undertake this kind of investment." Dhawan says industry is struggling for survival and cannot make the necessary investments. "The government will have to subsidise it," he adds.

Air unbreathable

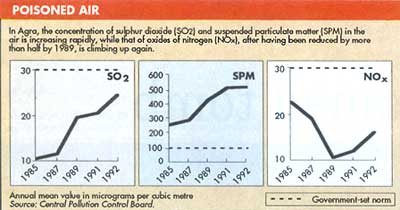

Under pressure for conventional economic growth, it is not surprising that recent CPCB data shows the air about the Taj is unbreathable. Sulphur dioxide has risen 66 per cent in little more than a decade and at this rate will exceed next year the MEF-set limit. SPM already exceeds the MEF norm and continues to rise. Nitrogen oxide has been rising steadily since 1989.

However, ASI director of conservation A C Grover denies that suspended particles are a problem "as they make the monument look dirty only temporarily", and he describes sulphur dioxide as "within limits." Senior MEF officials, however, while maintaining that there is no immediate danger, admit the need for action because of the rising trend of pollutants.

Industry accusations

Nevertheless, industrialists maintain their growth has been stunted -- and they have high-level support. Chaturvedi, for example, insists pollution is not a serious threat and says, "There is no growth in industries and no sales tax registrations are being permitted." And, to top all this, the Rajasthan State Electricity Board (RSEB) continues to press for permission to construct a 1050-MW, coal-burning power plant at Dholpur, just 65 km from the Taj.

The RSEB project was proposed in 1984, but has not received the go-ahead because of lack of agreement with the MEF on location, presumably because of the implications for the Taj. As it will require a broad-gauge railway line as well as water, eastern Rajasthan seems to be the most appropriate site for the plant. RSEB chairman R C Dave says in exasperation, "People had better learn to light their houses with candles and lanterns, because environmentalists will not let me produce power." And, another RSEB official asks rhetorically, "What does the nation need more -- a few foundries at Agra or a power plant at Dholpur?"

As with many of the issues in the Taj debate, the phrasing of the question circumscribes discussion. Perhaps the nation needs neither foundries nor another power plant. Perhaps it needs a power plant, but not at Dholpur and perhaps it needs foundries, but with adequate emission controls. Some of the choices may be expensive, but much of the bill will be paid by the Taj. Arun Dang, secretary of the Tourism Guild of Agra, estimates about 19 lakh tourists visit the Taj every year and their spending supports 20,000 families in the city.

Naqshband estimates annual foreign exchange earnings from the Taj at Rs 150 crore, with domestic tourists adding another Rs 50 crore of revenue to such businesses as hotels, restaurants, transport and handicrafts. Despite a low occupancy rate of 45 per cent, Agra's 1,500 hotel rooms are scheduled to be augmented by another 1,000 in the next two years.

The earnings could be even greater. The entrance charge to the Taj of Rs 2 each could easily be increased, especially for foreigners, and Chaturvedi suggests that offering entertainment in the evenings would encourage visitors to stay longer. At present, one-third of them leave Agra on the same day because there is nothing to do in the city after sunset.

Advocate M C Mehta, who has renewed the Taj debate by filing a public interest case to protect the monument, cites these tourism industry statistics to back his point that "earnings from the Taj can finance a refinery every alternate year". But to do so, Mehta points out it must be protected and this, he contends, is not being done. "The Taj is in a very bad shape," says Mehta. "I had to file the suit as the conditions were getting worse." Mehta asserts both inner and outer surfaces of the Taj are being damaged both by pollution and fungal deterioration. Mehta wants all polluting industries to be moved away from the Taj and an independent committee formed to monitor pollution continuously, with its findings made public periodically.

Even former ASI director general Thapar, apparently confident that all is well, was flabbergasted when Down To Earth showed him the new CPCB pollution figures. "It does not need any words," he commented. "The numbers speak for themselves. The ASI should not play down the threat to the Taj." But Grover rebuts criticism that the Taj has been neglected, saying it is well-tended and absolutely safe. But ASI joint director general K N Dikshit concedes no assessment of the Taj's condition has been made since a report by an Italian company, Teneco, in 1976. He wants such surveys to be carried out regular intervals.

Safety levels

There is no agreement among officials on when pollutants become dangerous. ASI is still seeking to understand the dynamics of how pollutants affect the Taj and so is in no position to set safety levels. ASI scientists, for example, disagree on whether long-term averages of sulphur dioxide concentration are an indication of the rate of sulphation, with some arguing sulphation may not be linear. The method for measuring sulphation gives the maximum possible reaction that can take place, but it is not an indicator of what is actually happening to the marble.

Noting that physical reactions can be slow, ASI science director R K Sharma says, "Our knowledge is inadequate to have any modelling done for a laboratory experiment in which the study of reactions in accelerated conditions is possible." The formation of sulphuric acid from sulphur dioxide, for example, varies according to meteorological conditions and the concentration of other pollutants in the air. The mere presence of sulphur dioxide is not the sole factor.

For ordinary buildings, sandblasting is the usual remedy for sulphation, but that is not an option for the Taj. So experiments are being conducted on re-polishing the marble surface to restore gloss and reflectivity.

Furthermore, marble is not the only material that has to be protected. There are iron dowels, plaster and a variety of semi-precious stones used for inlay work. Even the quality of marble used is not uniform.

No protective coating is being used on the Taj, and Sharma holds out no hope that suitable protection would become available soon. Existing coating materials would take so long to dry on non-porous marble that dust and insects would get stuck to the surface, reducing its sheen. In the long term, says Sharma, unless treatment breakthroughs occur, "reducing pollution is the only answer." But some ASI engineers argue significant developments have occurred and effective protective coatings are now available. Thapar, however, warns using chemicals can have irreversible effects, which may not be known until decades after their application.

Dikshit points out the ASI "does not have any executive powers to control pollution and has been taking up the issue with government departments." The minimal response to such approaches is typified by the UPPCB's May 5 reply in court to Mehta's suit. It provided a list of industries in Agra, as required, but no details of brick kilns, generators or traffic. So, while it has complied technically with the court's instructions, it has failed to present a complete picture.

Meanwhile, it is certain that Agra, its industries and their emissions will continue to grow. What is equally certain is that a long-term solution to the problem of protecting the Taj is still eluding the nation.