Fisherfolk thwart bid to reclaim wetlands

Fisherfolk thwart bid to reclaim wetlands

FOR THE 400 families belonging to the Mudially Fishermen's Cooperative Society (MFCS), Justice Shyamal Sen's order in Calcutta High Court on June 14, 1993, was a tremendous relief for it restrained the Calcutta Port Trust (CPT) from filling up or damaging in any way an MFCS-run wetland nature park that was renowned internationally. For more than a year, the MFCS families had been fighting to protect the nature park and also their livelihood because the CPT sought to require the wetland and convert it into building lots.

The success of the fisherfolk's unique cooperative is because of the enthusiasm of the members, who identify totally with their organisation and do all jobs related to it in rotation. Even MFCS directors never hesitate to strip to their shorts and help to draw nets when it's their turn to do so. Tapas Patra, 33, a commerce graduate from Calcutta University and now a first-year law student, works as a casual labourer for MFCS and is paid Rs 20 a day.

He is amazed when asked whether he minds being an ordinary fisherman, though he is highly educated. "It's our own cooperative society," he explains. "We own it, so why should I mind working as a labourer? All of us are its labourers, and we do all kinds of work by rotation. We work for ourselves." Patra explained MFCS pays for his education and for all other MFCS member wanting to study. In fact, he disclosed, primary education has become compulsory, not by administrative fiat but through social pressure.

The MFCS is located in the densely populated Taratolla-Hyde Park area, about 20 km southwest of the heart of Calcutta. It involves 80 ha of wetlands, leased from the CPT. By recycling waste water containing urban and industrial effluents through an indigenous bio-engineering system, the MFCS not only supports about 400 fisherfolk, but has also built the nature park amid foul-smelling factories and grey concrete jungles.

MFCS director Ashok Patra, 32, traces the cooperative's history to 1942, when their fathers migrated to the Metiabruz wastelands, near the Calcutta docks, from their ancestral homes on the Damodar's banks in Howrah district. "I have heard that the Damodar had silted up, making fishing difficult," says Patra.

A prosperous trader, Sudhir Banerjee, whose hobby was angling and who had leased the wetlands from the CPT, provided the migrants with some employment. In 1952, the fisherfolk formed a society and leased more than 250 ha of wetlands in the area from CPT for a payment of Rs 6,000 for six months. At that time, the CPT considered the wetlands unusable, but the fisherfolk toiled day and night and within five years they cleaned out all the weeds and recovered the area for fishing. Patra says the CPT promptly terminated the fisherfolk's lease and then leased it out to a rich zamindar from Nadia, S Pal Choudhury, at a much higher fee.

The CPT action, according to Patra, pauperised the fisher-families, but they still would not give up. Their leaders asked MFCS members in 1958 to deposit 25 paise per day and this resulted in an annual collection of Rs 4,500. Meanwhile, owing to neglect, productivity of the CPT wetlands began to decline and MFCS was able to exploit this factor to bid successfully for a six-month lease in 1961 for payment of Rs 26,000. "The money was raised through loans, recalls MFCS member Ratan Pakhira. "Jeevan Pakhira, one of our leaders, had to pawn his wife's jewels. The lease was given on condition that a cooperative society be registered and this is how MFCS began officially." Its first job, he says, was to get rid of the anti-social elements who were infesting their area.

Over the next two and a half decades, MFCS dragged on somehow, getting its wetlands lease renewed regularly. The fisherfolk lived in constant fear of losing their livelihood due to the increasing population pressure, industrial wastes and the silting of the wetlands. The CPT also reduced the leased area almost every year, appropriating the land for factories and docks.

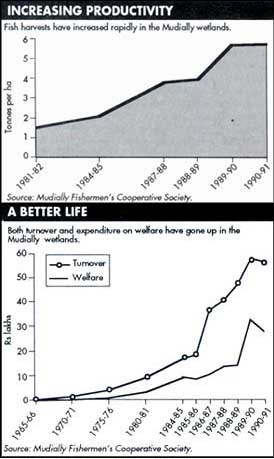

The turning point reportedly came in 1985, when Mukut Roy Chowdhury, a young official of the West Bengal fisheries department, because chief executive officer of the MFCS. Roy Chowdhury, who had experience in operating cooperatives in other parts of Bengal, worked long hours with the fisherfolk, organising them and developing with them a scientific fisheries system based on biotically recycling waste water. This led to both control over the wetlands environment and community commitment and involvement. Membership of MFCS rose from 101 in 1980-81 to 277 in 1990-91, and its turnover increased from Rs 9.35 lakh to Rs 58.10 lakh over the same period. The daily fish catch amounted to one tonne.

MFCS has three categories of members, though all are fisherfolk by occupation and by caste. The categories are permanent members, associate members and nominated members, the last mainly labour. All are paid daily wages ranging from Rs 20 to Rs 51, plus bonuses, education and medical expenses and gratuity. Other than voting rights, there is no difference between permanent and associate members, and casual workers can qualify for associate membership after two or three years of satisfactory work.

But housewife Mira Pahkira maintains that MFCS "still has a lot more to do. Women have not been involved, although efforts are going on." Other members agree and point out that in the wetlands of east Calcutta, where MFCS-inspired community organisations have been set up, women are already being involved. MFCS spends a lot of money on welfare activities. It has its own three-storeyed building, housing its office and a consumer store. The nature park features deer and rabbits and attracts many species of migratory birds in the winter. It is a favoured recreation site for city residents. MFCS has undertaken a massive afforestation programme, under which one lakh saplings of 78 species have been planted. About 30 per cent of the plants are of the leguminous variety like subabul. As these have been planted near the fish ponds, nitrogen-rich leaves fall into the water and supplements the nutrients of the fish culture. Another 30 per cent of the plants are neem and akand, which absorb dust and toxic grime. Bird-attracting myrobalans constitute another 30 per cent of the plantings but these are located away from the water bodies as their leaves and fruit make the water acidic. The rest of the trees are horticultural varieties. "All this has been done from our own funds," says Patra. "We don't believe in borrowing."

Ingenuous recycling system

MFCS recycles waste water through an ingenuous system of feeder channels and six ponds. On an average, about 23 million litres of sewage water, 70 per cent of which is industrial waste, are collected in the first pond, which is an anaerobic tank where the water is lime-treated manually. Water hyacinth are kept near this tank to absorb the oil and grease in the effluent and the tank is dredged often to remove sludge deposits.

In the second tank, into which water flows through a narrow opening to reduce silting, hardy fish species, such as tilapia, nycotica, singi, magur and koi, are bred. The water then flows into the third, fourth, fifth and sixth ponds, with water quality improving at each stage, and finally through the Manikhal canal system into the Hooghly. A well-equipped laboratory exists in the nature park and the workers there have been trained to check water quality. If the effluent level is too high, the water can be run the entire cycle again.

MFCS' fish catch is auctioned to retailers early in the morning. Says MFCS chairperson Shambhu Nath Mandal, "We make a profit, but that's not our sole motive. In 1989-90, when a fish disease took many lives in Calcutta, we increased our own consumption of the fish so that we could investigate the disease. We also undertook the responsibility for treating anyone who became ill after eating our fish, but nobody reported falling ill. There was a shortage of fish in the market, but we didn't push up our prices."

MFCS is committed to the cause of the poor. In one corner of the nature park, there is a slum and the producer of the film City Of Joy apparently wanted to flood it to stress the poverty of the slum residents. Says Patra, "Our response was a stony silence, which must have puzzled them."