Small towns Big mess

Small towns Big mess

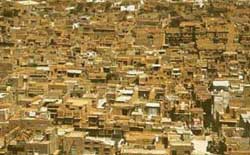

For a long time since Independence, Indians almost forgot that thousands of small towns lie outside the metropolitan veil. Such towns it seemed were destined to remain in the shadows of mammoth cities like Mumbai, Delhi, Chennai, Calcutta, Hyderabad, Ahmedabad or Bangalore. National discourse rarely veered round to minor towns and how to plan for them. The intelligentsia generally tend to think about an India that exists either in the metropolitan cities or the other end of the spectrum, the villages.

This lack of care has slowly become a major problem. In the last two decades, the towns began to grow out of the shadows of the metros. Tirupur in Tamil Nadu, Ludhiana in Punjab or Jetpur in Gujarat, industries sprouted and exports grew. As their products started making an impact in the market, the small towns woke up to their own potential. They found a place on the industrial map.

In order to find out what is the state of the environment and human life in these small towns, the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) studied the state of four industrial towns - Ludhiana, Jetpur, Tirupur and Rourkela, three relatively non-industrial towns - Aligarh, Bhagalpur and Kottayam; and Jaisalmer, a tourist town. The finding was shocking: India is facing a total and absolute collapse of its urban environment.

Every non-metro that CSE studied revealed already appalling and worsening conditions. There was no organised civic effort to change anything. Almost as if India's emerging elite in these towns has reconciled itself to the filth in the same towns where their magnificent mansions had come up. The civic authorities seemed mesmerised by the process of change and were dwarfed by its scale.

There is no dearth of irony in the way these towns are managed. For example, Bhagalpur has no sewage and, not surprisingly, it is drowning in filth, mostly domestic waste. But Aligarh has a sewage system. It should have been a clean city. But Aligarh too is drowning in filth from overflowing sewers. Wbere we don't have sewage systems, we point to that as the cause of dirt and filth. Where we have sewage systems, we don't know how to keep it functioning.

Towns like Aligarh and Bhagalpur are poor towns. They have not benefited from industrial investment but they are cracking under the pressure of a growing population. These towns have no waste disposal systems, and have subsequently been drowned in filth. But towns like Ludhiana, Jetpur, Tirupur and Rourkela are industrial boom towns with lots of money. Ludhiana's municipality, for instance, has a budget of Rs 100 crore. But the result is the same: mounting wastes, crippling traffic and unchecked industrial pollution. The ultimate irony is that progress has only meant one more step towards catastrophe.

Due to lack of good drinking water, people are forced to use groundwater which results in a reduction of the ground-water table. Toxic wastes are known to be polluting the aquifers in these towns. In Ludhiana and Tirupur, there are reports of rogue industrialists even pumping their toxic waste water into groundwater aquifers to escape detection by pollution control inspectors.

As water has the unique ability to collect all the dirt and the filth generated by society, an excellent indicator of urban decline is the state of all the rivers and streams that pass through the minor towns that we studied. No town that CSE studied passed the test. The Buddah nullah (canal) which passes through Ludhiana and feeds the Sutlej, the Bhadar which passes through Jetpur, the Noyyal which bisects Tirupur and the Brahmani which meanders past Rourkela have all been laid waste by chemical and microbiological dirt produced so abundantly in these places.

The people of Dhoraji living downstream of the river Bhadar in Jetpur and farmers living near Tirupur have filed cases against the polluters upstream. Though the judges have threatened closure of the polluting enterprises upstream, precious little has changed. This is the only sign of organised protest that CSE noticed. But there were no protest within the polluting towns themselves. Voluntary organisations pushing for change were non -existent in this landscape.

This crisis of urbanisation cannot be met by just building a drainage system for every growing town. The larger questions of resource crunch, infrastructure and migrating populations have yet to be addressed in a focussed manner. Then, of course, there is the problem of bureaucracy which does a lot of planning (master planswhich serve no purpose but look good on paper) and does not implement anything. And then there are no ideally managed towns which can spread their good tidings through ripple effect or from where other town planners can learn a few lessons.

At the heart of it aft is a cultural crisis. In all these towns selfishness has reached a peak. Indians are happy to keep their houses clean. But they are equally happy to live with filth around them.

Money or no money, plan or no plan, these towns seem destined to wallow in filth.