When the old gods died

When the old gods died

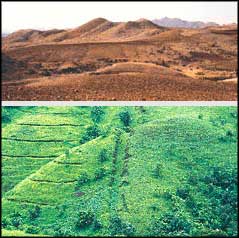

this is an amazing story. A story that shows that India can start eradicating poverty very fast and very cheaply. This is the story of the degradation and the regeneration of Jhabua - a poor tribal district of Madhya Pradesh bordering Gujarat. In 1985, when I first visited the district, I thought I had been catapulted to the moon. The degradation was just extraordinary. In 1986, when Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi asked me to address his Council of Ministers and subsequently all the 27 Parliamentary Consultative Committees attached to various Union ministries on the state of India's environment, I began all my presentations with the moonscape of Jhabua. "Beware," I used to say. "This is what India is becoming." One minister even said, "Agarwal, you are showing us pralaya (the end of the world in Hindu myths)."

Therefore, when Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Digvijay Singh, whom I have never met, said that he would be happy to release our latest report on the state of India's environment which focuses on traditional water harvesting systems but that he would like to do so in Jhabua, I readily agreed, because it was over a decade since I had been there. When the time came to go, I was quite unwell and stayed back while my colleague, Sunita Narain, took the train. But Digvijay Singh, who was in Delhi, suggested that I take his plane to go to Jhabua. As I could not say no to his kind gesture, I got out of bed after a two-week-long bout of bronchitis and high fever, and went. On the plane were some senior politicians of the Congress party. The discussions revealed a sense of despair about the state of the country. One of them even said, "Just tell me, even if you or I were to become the prime minister, just what is it that we can change?"

I, therefore, landed in Jhabua feeling dismal. But the rest of the day made me a new man. After the release of the book in front of over 500 village people involved with watershed development, I returned the plane and decided to visit a few villages before I made my way back by car to Indore that night. What I saw was astounding. Instead of a moonscape, there was a land being nursed and being brought back to life with great love and care. Trees were beginning to grow and there was green grass all around. There was good coordination amongst the district officials. And the villagers had formed village-level committees to take charge of the watershed development work. They proudly talked of the enormous benefit they were already reaping because of the increased availability of grass. I asked the district forest officer, "But just what did you do to allow these poor villagers to take control of the management of government forest lands? What laws and rules did you amend?" He stared back at me blankly. "Why, what is the problem?" he asked. I retorted, "But all over the country forest departments just don't allow villagers access to the management of forest lands. It is the most contentious issue in forest management." He still stared at me blankly as if I was asking a meaningless question, which indeed in many ways it is.

I soon understood the reason. The watershed programme in the state is supervised directly by the chief minister (see box: Mission control). Given the political will behind the programme, bureaucratic rigmarole which stifles millions of other innovative efforts, just did not figure in Jhabua. In addition, the chief minister has chosen a bureaucrat who knows the subject to coordinate the programme, unlike hundreds of generalist administrators who don't know or feel anything about anything. On the other hand, R Gopalakrishnan, who was district magistrate of Jhabua in the mid-1980s when the land was reeling under massive and successive droughts, became so interested in land management that he took time off to do a master's on the subject of poverty and environment in usa. In the interim he also took a keen interest in a paper that Sunita and I had written called Towards Green Villages in which we had identified the key lessons of success stories like Sukhomajri in Haryana and Ralegan Siddhi in Maharashtra. Gopal wanted to go ahead and do a PhD on the subject when Digvijay Singh asked him to coordinate this programme. Gopal took to it like a fish to water. The result: there is rapid regeneration because of the combination of water conservation together with afforestation and natural regeneration, at a cost that is unmatched by any afforestation programme and with no new addition of government babus.

Jhabua is a dramatic story because of the three key ingredients that are missing in most government programmes: political will, competent and committed bureaucratic support, and people's participation. Every politician in India talks about eradication of poverty. But there is not one, I repeat, not one, who knows what to do. The story of Jhabua shows that a beginning can be made and made quite fast. It is a story that people like Atal Behari Vajpayee, Sitaram Kesari, I K Gujral and a host of others should read like a primer. Whether these lacklustre leaders will do so, I do not know. But Jhabua does show that there is no need for dismay. All that is needed is a sense of challenge. My congratulations to Digvijay Singh and Gopal.

After coming back, I sent Down To Earth reporter Richard Mahapatra twice to Jhabua to further investigate its turnaround. I hope his story inspires our readers as it has inspired me. Maybe one day Richard, who comes from Orissa, will do a sequel on why Jhabua is working whereas Kalahandi, with exactly the same kind of ecological and social conditions, is not.

Anil Agarwal