Child workers want their unions recognised

Child workers want their unions recognised

EVEN AS international pressure mounts on India to improve the lot of its child labourers, the Delhi High Court has ruled against children forming trade unions to protect themselves against exploitation. In February, the court dismissed a petition by the Bal Mazdoor Union (BMU), a union of working children in Delhi, challenging the refusal of the registrar of trade unions to recognise it. The BMU has decided to appeal the High Court's ruling.

The BMU's plea for registration in April 1992 was turned down because section 21 of the Trade Union Act of 1926 states no one below 15 years can join or form a trade union. The BMU, which was formed in January 1992, moved the court on the grounds that the Trade Union Act excluded children because child labour was totally prohibited at the time of its formulation. But in 1986, when the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act came into being, it "legitimised child labour by banning it only in a few hazardous industries mentioned in the Act," contends BMU spokesperson Rita Panicker. And, she argues, the legislation can be effectively implemented and working children's rights protected only if trade unions are formed. "At present the 1986 Act is being observed more in its violation," she says.

The court ruling Judges J Chowdhary and J Shamins, however, ruled children could not be entrusted with the right to form a union as they were not competent to contract among themselves. The court also rejected BMU's contention that the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, ratified by India in November 1992, clearly recognised children's right to form associations.

The National Child Labour Policy also reiterates the government's determination to "protect children against neglect, cruelty and exploitation". However, says Panicker, "in reality, a double indignity has been inflicted on child labourers. Instead of being in schools, they are being made to work, and when they seek judicial avenues to assert their fundamental rights reinforced by several international commitments, this is denied to them as well." She also says that as a signatory to the UN convention, the Indian government is obliged to amend its laws accordingly. "But the government is indulging in double talk -- In international forums it agrees children should have the right to unionise, but within the country it refuses to register their union."

But Vasudha Dhagamwar of the Multiple Action Research Group (MARG) disagrees with Panicker's argument and says giving working children the right to form unions would amount to perpetuating child labour. According to her, though the problem of child labour has arisen because of contradictory legislation, "urgent attempts should be made to work towards its abolition", adds Dhagamwar.

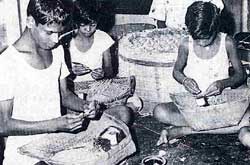

Panicker dismisses Dhagamwar's argument saying, "Despite all efforts to wish away child labour, there are more than 17 million child labourers in India." Delhi alone has more than four lakh children working in miserable conditions in industries, including those classified as hazardous, and their number is increasing. "When we cannot abolish child labour, we must improve their working conditions and trade unions all over the world have helped improve the plight of workers," says Panicker.

All India Trade Union Congress secretary P N Siddhanta agrees with Panicker. He contends that as child labour was not likely to be eradicated in the near future, it is all the more necessary to ensure children were not exploited. And this, he says, can be best achieved by unionising them.

Stand unclear

Interestingly, the Union government does not seem to have any clear stand on the issue. Though the subject concerns at least two ministries -- welfare and labour -- officials at both ministries expressed their ignorance about the judgement. Shashi Jain, joint secretary in the labour ministry, says the judgement has not come to her notice, but "as such the government policy is to gradually eliminate child labour, and unionising them would be to take a different line altogether". Asked whether labour unions would not improve working conditions for the children, Jain was noncommittal.

Welfare ministry deputy secretary Amitabh Rajan also refused to "comment without studying the subject carefully".

Panicker, who also heads a welfare programme for street children in Delhi called Butterflies, says international attention was beginning to focus on the plight of Indian child labourers, particularly because of the government's apathy towards them (See also: Building self-reliance in children of the street). "If the government does not get its act together to ensure at least reasonable working conditions for children, it may invite drastic sanctions," she warns.

According to a senior official in the welfare ministry, several major American and European importers have made it clear they will not buy products from manufacturers who employ children. US senators are reportedly planning to introduce a bill -- the Child Labour Deterrence Act of 1993 -- that seeks to ban import of goods made by children. This could have drastic results on the Indian carpet industry where most of the work is done by children, and over-exploitation of child labour is said to be the main reason for the price advantage Indian carpets enjoy in international markets.