Cure before birth

Cure before birth

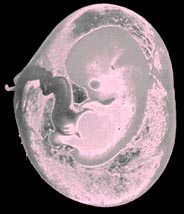

IN WHAT is described as a medical first, a four-month-old foetus, genetically doomed to have a disastrously weak immune system, as he was diagnosed to have severe combined immunod- eficiency (SCID), was successfully given a bone marrow transplant while in the womb. The foetus was administered marrow cells from his father at 16, 17.5 and 18.5 weeks of gestation. So at birth, all his T-cells were of paternal origin while B-cells, monocytes and natural killer cells were his own. The baby was born healthy and is about 18-months old now and has so far shown no signs of the inherited disease. In addition, one year after the last transplantation, there was good immune and cellular reconstitution and persistence of the father's cells.

SCID, first described in the '50s in Switzerland, is fatal for infants. Little was known about the disease, which is more common among boys, and part of the mystery could be solved only during the late '70s, largely due to fresh findings about T and B lymphocyte markers.

Among the several new methods tried out to cure SCID, bone marrow transplants are by far the most popular and perhaps the most successful. All babies with SCID are given bone marrow transplants shortly after birth. When things go well, the transplanted marrow produces the blood cells that the babies lack. But in about a third of such cases these efforts fail.

The transplants in the womb were carried out at the Children's Hospital in Michigan, US, by Alan W Flake, a paediatric surgeon and his colleagues (New England journal of Medicine, Vol 335, No 24). This approach was especially noteworthy because it prevented the fatal disease even before it made its appearance. The researchers chose to attack the disease while the baby was still in the womb because administering such cells in the uterus reduces the risk of rejection as the immunologic system of the foetus is still immature.

There were other advantages as well. In the normal course of treatment after birth, infants have to be given powerful drugs to destroy some of their marrow which could cause toxicity as well as destroy vital tissue. But when the marrow is implanted while the baby is in the womb, such a step is rendered redundant. Also, babies who arc to be given bone marrow itransplants have to be kept in disease- free environments for three to four months before the commencement of treatment. This also is rendered redundant as the womb provides the best natural germ-free environment.

The boy who received this implantation in the womb is the second son of a woman who carried a mutant gene that results in this disorder. Her first son died seven months after birth. Doctors did the genetic testing when she became pregnant again. They found that this foetus too had the bad gene.

Once the doctors expressed their interest in trying out this experimental therapy, the family decided to take a chance to allow them to fix the genetic defect before birth. Luckily for the parents, the infant given marrow from the father was born normally. Since birth, the boy has had two bouts of cold and has recovered normally. More importantly, his blood carries the usual number of T-cells that ward off infections.

Elaine Glickman from the Hospital Saint Louis, France, hails it as a significant step towards combating SCID. William Shearer, the boy's physician, calls this treatment an important advance as it opens up an entirely new avenue for therapy and, therefore, survival of SCID kids. Mercifully, its incidence is rather low - affecting about one in 100,000 kids.