Energy aplenty

Energy aplenty

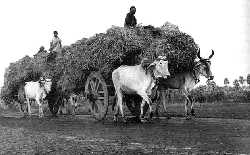

while plants like sugar cane and wheat store about 10 times the energy the world consumes annually, only about 13 per cent of the world's total energy comes from their use. A large and renewable source of energy is thus left untapped or wasted. A small entrepreneur, Satish Raut, from Rahuri in the Ahmadnagar district of Maharashtra has developed the technology of manufacturing coal pellets out of an agro-industrial waste, bagasse and an agricultural waste, wheat straw to create a non-conventional source of energy.

These pellets, christened 'biocoal', is superior to hard coke on many counts. The ash content is only seven to eight per cent, much less than in hard coke from Indian coal mines. The ash content of Indian coal is notoriously high and creates the ever worsening problem of disposal of fly ash, which accumulates in very large quantities near thermal power houses.Biocoal also does not contain sulphur, another atmospheric pollutant, and its calorific value is about 4,000 to 4,200 kilo-cals per kilogram, almost the same as hard coke. Over and above, the cost of biocoal production is less than that of hard coke. A small scale industrial unit set up with approximately Rs 75 lakh, can produce 10 tonnes (t) of biocoal every day and with slight modifications to the machinery, the production can be raised to about 40 t a day.

It is possible to establish many such units in the sugar producing states of India where bagasse is a daily by-product. As of today, sugar mills in Ahmadnagar district obtain their supplies of coal from Chandrapur collieries, and spend a fortune on transporting it to the sugar mill. While earlier, bagasse was simply burnt away in fields by farmers, today it is used for making newsprint. But the number of paper mills making newsprint out of bagasse is very small and they are also not situated close to villages growing sugar cane and making jaggery out of it.

As a result, a very large amount of bagasse accumulates with the sugar cane farmers. The bagasse does not decompose into compost quickly and, therefore, it is not possible to leave it in the fields for long. Large quantities of bagasse are finally burnt away in fields. The burning process not only pollutes the atmosphere but also kills earthworms in the farmland.

Making biocoal involves solidifying agricultural waste like bagasse and wheat straw through the process of pelletisation. It may also be possible to use other agricultural wastes like soyabean, cotton and arhar (a variety of pulse) stalks, which are also burnt away at present, for want of an adequate technology to convert them into coal pellets for domestic and industrial use. The biocoal pellet is admirably suitable for paper mills, sugar mills and industrial boilers as well as brick kilns currently using hard coke. The Maharashtra State Energy Development Authority has a plan to set up a 100 mw thermal power house using the biocoal.

Farmers in Ahmadnagar district alone burn about 0.8 million tonnes (mt ) of baggase and wheat straw each on an annual basis. The figures for the country as a whole could then be mind-boggling. The amount of bagasse produced in India is estimated at about 50 mt with its sources scattered throughout the sugar producing states of India like Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra. Similarly, the sources of wheat straw lie scattered throughout the length and breadth of the country. If all this agricultural waste were to be converted into biocoal, then the energy scarcity can be easily met.

A pilot project of the Department of Science and Technology under the Union government, for manufacturing about 80 t per day of fuel pellets from refuse as a substitute for coal, has been set up at Mumbai. The technology being used is totally indigenous. The pellets are about four cm long with a diametre of two cm, ash content of five to 10 per cent and have a calorific value of 3,500 kilocals per kilogram.

The indigenous technology has potential for easy adoption in other cities of India producing vast quantities of refuse every day. A number of wood substitutes can also be made out of agricultural wastes. A Haryana-based company has put up a plant to manufacture a substitute for wood out of these agro-wastes. nuwood, as it is called, can be worked in the same way as wood, treated and finished the same way as timber. It can also be carved like walnut and teak. It is necessary to establish such units in the cotton and arhar growing regions of India like Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh.

Engineers working at the Indian Plywood Research Institute, Bangalore, have developed the technology of making particle boards, suited to Indian climatic conditions and requirements, out of rice husk, another agro-waste. These can be used as false ceilings, cabinets, almirahs and door panels. With many such industries coming up to utilise agro-wastes, perhaps the earlier detrimental method of burning them and causing atmospheric pollution will be a thing of the past.

Setting an example

The practice of burning cane trash before harvesting the cane fields has been prevalent in Tanzania for some time now. These wastes have an energy equivalent of up to 10 barrels of oil per hectare. In many developing countries, this energy can be used to reduce dependence on fossil fuels as well as reduce the negative effects of global warming.

A study at the Tanganyika planting Company (tpc) sugar mill in Tanzania, illustrates the possibilities of increasing power generation in a manner that is both economically and environmentally advantageous (Renewable Energy For Development, Vol 8, No 2). Four options were outlined to increase the generation of electricity at the tpc according to Mohamed Gabra of Lulea University of Technology, Tanzania.

These include: use of cane trash at the existing factory during the off-season; a new system with a more advanced steam process; a combined cycle consisting of a gas turbine and back-pressure steam turbine using bagasse and cane trash and a combined cycle consisting of a gas turbine and condensing-extraction turbine, also using bagasse and cane trash as fuel.

In a pilot study, the tpc sugar mill in Tanzania was selected for investigation. At present, a turbo-alternator, rated at 2.5 mwe, generates an average of 1.9 mwe, which is sufficient for the internal power requirements of the sugar mill during the milling season. On an average, about 76 per cent of tpc's electric energy consumption is purchased from the Tanzania Electric Supply Company. This purchase is a significant financial burden, amounting to about 30 per cent of operating costs for the steam plant.

Today, all the bagasse and some supplementary fuels are used to generate electricity and process steam. Generation of energy for irrigation and possible sale to the national grid would require increased process efficiency or the use of an additional fuel such as cane trash. Analysis of the four options has shown that by increasing the steam pressure and the steam temperature to about 520