A long line of woes

A long line of woes

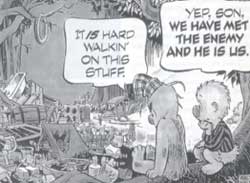

WE HAVE met the enemy, and he is us." This line, from the well-known 1960s US comic strip Pogo by Walt Kelly, still retains its topicality today as a comment on our contribution to environmental degradation. Our insatiable appetite for 'progress' has ensured the extinction of countless life forms, and those that have survived the human onslaught are facing a bleak future. Still, once in a while, we do take notice of the damages we have done, and try to undo some of these.

In one such conscience -driven move, fisheries scientists recently came together to approve a United Nations (UN) plan to protect hundreds of thousands of albatrosses and other seabirds that die a grisly death every year from fishing boats which use longlines.

Longlining is a commercial extension of conventional angling. Fisherfolk pay out lines often more than 30 km long from the stern of large fishing vessels. These longlines carry thousands of baited hooks and though intended for the fishes, many birds get tangled in these hooks and are dragged under. This happens because before sinking eventually, the bait can float on the surface for up to 50 m behind the vessel. And before it can sink, many birds gather to 'grab' the bait and subsequently die a very painful death.

In some cases, birds take more than half the bait. Victims of these tragedies often include endangered species like the wandering albatross of the Southern Ocean, which loses 10 per cent of its population annually to these longlines, and fulmars and gannets off Europe's Atlantic Coast (New Scientist, Vol 160, No 2159).

The 1990s witnessed a sharp increase in longlining, and it is currently used to catch a host of fish including tuna, swordfish, hake, ling, cod and Patagonian toothfish. Ironically, longlining was the so-called alternative to another environment- damaging fishing method: the use of giant drift nets, often dubbed as "walls of death", as they swept up countless unwanted fishes, dolphins and birds.

The meeting, held at the headquarters of the UN Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO), in Rome, Italy, finalised a plan to protect seabirds from longlines by encouraging fisher folk to equip their fishing vessels with such devices that will prevent the birds from becoming hooked and killed. The plan should be adapted by governments sometime in 1999 under the FAO'S Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. Similar exercises have been carried out in the past when large-scale losses in populations of olive-ridley turtles in Orissa, India, were reported. Though the Indian government was urged to make the use of turtle excluder devices mandatory for all local fishing vessels, precious little was achieved. However, one can only hope that this time, the concerned nations will take the required steps.

"It will not be legally binding, but it will give a strong steer to governments about what to do," says Euan Dunn, marine policy officer in Britain for Bordlife International, one of a number of conservation organisations campaigning for new fishing rules.

One technique that enjoys the full support of the conservationists is a simple steel tube, about four metres in length, through which the line passes from the ship to the water. It shields the bait from the birds and helps push the line under the surface.

"Trials on a Norwegian boat this year have been extremely promising," Dunn stresses. "It makes the line invisible and inaccessible for the birds. The only problem may be the deep-diving birds in the Southern Ocean such as petrels."

The tube is the brainchild of Norwegian longline manufacturer Solstrand, and, according to Dunn, is a great improvement on the only widely used method for scaring the birds - a glorified version of the rural scarecrow in the form of a pole covered with brightly- coloured strips of plastic, known as a 'streamer'.

Other methods discussed by the UN meeting include machines that throw the line to one side, away from the ship's wake, so that it sinks faster, the broadcast of bird distress noises and even the generation of magnetic fields to disorient the birds, which usually use their magnetic sensors to navigate. The US, Japan and the European Union have supported the moves, but objections are expected from Latin American nations such as Argentina, whose fishing vessels catch sizeable quantities of Patogonian toothfish in the Southern Ocean.