The rebirth of ancient wisdom

The rebirth of ancient wisdom

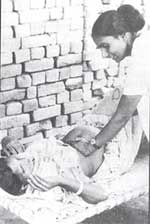

DAIS, those traditional Indian midwives both respected and feared as carriers of natal wisdom, deliver 67 per cent of the babies born in the country. They apply traditional skills derived from the ancient science of Ayurveda. The dai treats childbirth as a natural -- as against a scientifically-mediated -- process and has skills to help both the expectant mother and the newborn. A number of these traditional practices are now, after decades of doubt, being endorsed by modern medical research.

Even in the West, where paediatricians encouraged mothers to bottle-feed their young with milk substitutes, efforts now are being made to encourage mothers to breast feed their babies, as Indian mothers have been doing for centuries. In fact, the first week of August was declared World Breast-feeding Week by the World Alliance for Breast Feeding Action, an international public interest organisation.

Despite the spread of modern medicine, the dai still plays an important role in Indian society. A recent study by the Lok Swasthya Parampara Samvardhan Samithi (LSPSS), a Madras-based NGO, records some 600,000 dais in India. Another NGO, Social Action For Rural and Tribal Inhabitants of India (SARTHI), has documented the plants used by dais in Santrampur in Gujarat and found that 80 per cent of them have the necessary medicinal properties.

From abortion to childcare The service package of dais ranges from infantcare to abortion. In Himachal Pradesh, abortions are performed by removing the outer skin of Chitrak (Plumbago zayalinca) roots and inserting them in the woman's cervix. This dilates the cervix and the immature foetus, up to 3 months, aborts within 12 to 24 hours.

However, this practice has its problems. Says Arun Chandan, programme officer at the Voluntary Health Association of India in New Delhi and an expert on herbal medicine, "The root may become imbedded in the uterus and cause serious complications. Experienced dais attach a thread to the root to enable removal." A dead foetus is aborted by tying the roots of Aparang (Achranthus aspara) around the mother's waist. Although this method is effective, it is still not clear how it works.

Home prescriptions Pregnant mothers often consult the local dai on what to eat to ensure a healthy baby. "The diet advocated by dais during pregnancy is sound," says Chandan. Dais recommend a carefully worked out regimen for the whole period. Nausea, vomiting and indigestion can make life miserable for the expectant mother in the first 3 months. The dai's diet for this period consists chiefly of liquids like cold milk, honey, coconut water, small doses of pineapple, papaya and mulathi (liquorice). From the 3rd month onwards, rice with milk, ghee and honey is given. Shatavari (Asparagus recemoses) is prescribed to help increase breast milk.

From the 4th month onwards, a solid diet is recommended. The juice of pomegranates mixed with lime is prescribed to control nausea. From the 8th month, a digestive powder made with pipli (Piper longum), honey and lodha (Symplocas paniculata) is given to cure digestive ailments.

Unlike modern gynaecologists, who recommend that a pregnant woman lie on her back to deliver the child, dais encourage different postures during delivery. A semi-reclining or a squatting position is regarded as more conducive to an easy birth since it opens up the pelvic bones and enables the baby to slip out easily. The pregnant woman is instructed to "bear down" only during labour pains. Interestingly, some modern gynaecologists are realising the wisdom of the dais' ways. Says Santosh Sahi, an obstetrician, "Today more and more women avoid the routine high-tech approach and choose natural methods."

Dais remove the placenta either manually or by using different types of herbal mixes. The umbilical cord is generally tied with a string before it is cut. The instruments used vary from knives and sickles to bamboo chips. In Gujarat, dais feed the new mother a decoction of dodi (Leptadenia reticulata) leaves to prevent tetanus. In Kerala, a mixture of oil and turmeric is applied to the baby's navel to disinfect the wound. To cleanse a newborn's skin, an oil prepared with bala (Sida cordifolia) is applied.

Dais also assist in mothers to recover from labour and help manage the newborn. Mothers who bleed excessively after childbirth are given herbal decoctions of madhuka (Glycyrrhiza glabra), devadaru (Cedrus deodara) and manjishta (Rubia cordifolia). Massages with various kinds of herbal oils such as sarala (Pinus longifolia) or warm water medicated with nirgundi (Vitex negundo) or tulsi leaves (Ocimum sanctum) are recommended.

The lax abdomen is helped back into shape by bandaging it tightly. Normally, mothers are encouraged to start breast-feeding 2 to 3 days after delivering. Contrary to modern medical wisdom, most dais regard the mother's first milk, or colostrum, which is rich in infection-fighting chemicals, as "impure" and discourage mothers from feeding it to the child. Instead, the infant is fed honey or sugar mixed with water. The Ayurvedic view supports this practice.

Numerous baby ailments are handled by dais. Constipation is treated with a decoction of myrobalans (triphala) mixed with sugar or honey, colic pains with ajwain (Trachyspermum ammi) mixed with honey, and jaundice with neem leaves and honey or dadima (Punica granatum) juice with sugar. Tulsi leaves mixed with betel leaves and sugar is recommended for coughs. To treat worms, a powder made from the bark of the dadima root mixed with honey is given.

The dai's traditional practices are interwoven with rituals and a sympathetic attitude to the patient (see box). Says Chaturiben, a dai from Nanirel village in Panchmahal district of Gujarat, "In a hospital, a woman has to make all the effort herself. The nurses do not allow anybody to touch her. If she needs to sit or get up, she has to manage alone. At home, at least there are people to reassure her."

Mediating modern medicine

Says Chandan, "Several medicinal plants used by midwives are becoming extinct due to over-exploitation. Dais are not helped to propagate these species." Dais need help to better their skills in the proper abdominal examination of pregnant women, the use of antibiotics, contraceptives, the necessity of tetanus shots, and of hygiene. They can also be an excellent vehicle to effectively convey medical messages like infant weaning, immunisation, the importance of adequate iron and simple hygiene.

Given the importance of dais in the unorganised health sector, efforts are being made both by the government and voluntary agencies to upgrade their skills. Says Chandan, "Dais live in the villages, know the people well and are familiar with local beliefs. In the absence of conventional medical care, they provide an accessible and inexpensive medical service. There is a crying need to upgrade their skills and treat them as people of science."

SARTHI, for instance, has trained dais in Santrampur, Gujarat, in maternal and child care. By building on traditional beliefs and practices, SARTHI was able to update and hone old skills. The women were trained to provide nutrition education to pregnant women and lactating mothers and trained to immunise against tetanus. They were also trained in aseptic deliveries and child care. For complicated deliveries, SARTHI helped these women develop links with the government health system.

Several women in the villages where SARTHI was active felt that the health care provided by dais had improved after their intervention. However, government efforts to train dais have not met with the same success. Says Chandan, "Allopathic doctors are placed in charge of dais. They have almost no respect for these women and their traditional skills." Only sensitivity to local beliefs and practices and respect for the dai can usher in change. The dai is the original barefoot doctor. With better skills, she could hold the key to a healthier future.