The secret sex life of the sea urchin

The secret sex life of the sea urchin

AFTER three decades of dogged research, biologists have discovered how the sea urchin, a relative of the starfish, mates. They now hope this will help them solve some fundamental problems in developmental and evolutionary biology.

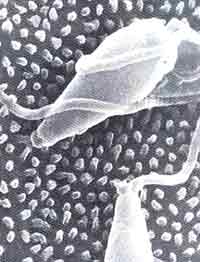

The sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus), like its other marine cousins, jettisons its eggs into the open sea to be eventually fertilised by sperm of the same species. But, the scientists reasoned, for this to be possible, the egg and sperm must send out secret signals that cannot be recognised by the eggs and sperm of other species.

In 1977, biologists looked all set to unravel the mystery when Victor Vacquier, now at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, California, identified the egg-recognising molecule on the sperm as a protein called bindin. But it was only recently that the sperm receptor on the egg surface to which this protein binds was discovered by a team led by William Lennarz of the State University of New York at Stony Brooks (Science, Vol 259, No 5100).

"It's been the hardest project of my 30-year career," says Lennarz. He got interested in the problem when he realised that the knowledge of how a virus enters a bacterium could serve as a guide to understanding how sperm "infect" eggs. When Vacquier discovered bindin, Lennarz figured that since the protein bound to a receptor on the surface of the egg, it could be used like a template (the molecular pattern governing the assembly of a protein, which is similar to the negative of a photograph) to identify its partner.

The discovery holds many promises. It has been suggested that the sperm receptor is probably responsible for the mechanism that galvanises a dormant fertilised egg into a frenzy of cell divisions that form the embryo. If similar mechanisms occur in the eggs of higher organisms such as mammals, scientists reason that sabotaging the mechanism could prevent births.

The discovery may also reveal something about how new species come into being. Scientists argue that the chance occurrence of both a mutant sperm receptor and of a mutant bindin that could recognise it, may have given rise to a distinct species of sea urchins that could no longer breed with others of their kind.