A zero effluent project

A zero effluent project

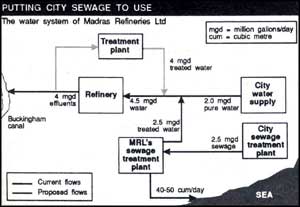

MADRAS Refineries Ltd (MRL) will soon be a zero-effluent company. Situated in Manali, on the outskirts of water-starved Madras, MRL plans to treat its waste water and pump it back for circulation in its cooling towers.

The Madras city corporation, which is extremely short of water, has placed restrictions on its use for industrial uses. Industries are also restricted from tapping groundwater reserves. Madras' total water supply is less than 66 million gallons a day (mgd). MRL needs 4.5 mgd of water -- 6.91 per cent of the city's daily supply. As a result, MRL is often forced into a water crisis, more so during the dry months. Lack of water has also prevented it from expanding its production facilities.

Recognising these constraints, in August 1991, MRL became the first Indian company to buy treated sewage from the city corporation for use in its plant. Since then, MRL's Kodungiyar treatment plant has been processing 2 mgd of water to meet its water needs. As the quality of this sewage varies enormously, the company has set up its own secondary and tertiary treatment plants.

The sewage treatment system is a reverse osmosis unit in which pure and impure water are separated by a semi-permeable membrane. The dirty water that is left behind in the reverse osmosis unit has a high salt concentration. Moses says, "This water -- at least 40 cum per day -- is let out into the sea through a pipeline that ends 1.2 km from the shore, following the recommendations of the National Institute of Oceanography."

Since even sewage goes out of supply at certain times, especially during the night, the refinery stores enough sewage to work the treatment plant on a continuous basis. An MRL official says, "We have built two tanks that can store 3 million gallons and 2.5 million gallons of sewage each."

MRL itself discharges 4 million gallons of treated industrial effluents every day into the Buckingham Canal. It now plans to set another tertiary treatment and reverse osmosis system to upgrade the treatment of these effluents and recycle them.

V Kaniappan, deputy general manager (manufacturing), says, "Once this system becomes operational, our water intake for the refineries will go down by 80 per cent." The new system is likely to be commissioned in the next six months at a cost of Rs 20 crore. But the refinery will save Rs 45 lakh every month on the purchase of pure water from the city corporation. Treated sewage is also more expensive than pure water -- 1.8 paise per litre against 1.2 paise per litre - but it gives the company less worries and chances for expansion.

There is further scope for water conservation, says S Ramalingam, director of operations at MRL, and adds, "Our objective is to commission a large common sewage treatment plant, which can meet the industrial water requirements of all the downstream industries in Manali."