Dying on the edge

Dying on the edge

flowing along the western edge of the Corbett Tiger Reserve ( ctr ) in district Nainital of Uttar Pradesh, the river Kosi has seen many humans being killed by animals. This time it was Bhawani Ram. His son Harsh, 17, sits on the bank after immersing his father's ashes. That was all he could do for his father. He was in Delhi, working in a bungalow of a posh south Delhi colony, when his father was killed. A barber shaves his head, in accordance with Hindu rituals. A priest chants a mantra , takes a handful of water, and pours it on Harsh's bare pate.

It has been two days since Bhawani died on October 10, 1998. A marauding elephant emerged from the surrounding forest and approached his paddy field at 1 am . Bhawani was sleeping on the machaan under a mango tree in his field when he was woken up by the tusker. He ran towards his house, about 50 metres away.He was not fast enough. The powerful trunk tightened around him. The pachyderm lifted his helpless figure into the air and threw him on the ground, then trampled him to death. Ramesh, a neighbour, recalls Bhawani's des-perate last cries. And now there is only the monotonous sound of water flowing in Kosi.

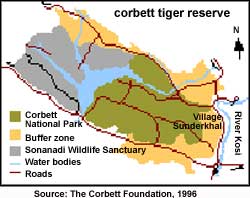

People living in villages in and around ctr have got used to such stories. Before 1973, when the forest was declared a tiger reserve, they could fend off the animals. "Earlier, we could defend our lives, cattle and crop. If needed, we could kill the plundering animals. Now, the animals are protected, we are not," says Urvadatt Simwal, a resident of village Dhekuli, which is not very far from village Sunderkhal, where Bhawani was killed. "The animals matter. We do not," says Bhuvan Ram, a resident of Sunderkhal. Animal attacks have increased recently. The Ramnagar division of ctr has recorded that at least 12 people were killed by tigers and elephants in the past 10 years. Forest officials say the problem has intensified as the villages have shifted into the migratory path of the animals. This happened as the river changed its course following recurrent floods, which claimed more and more fields and huts each year. Earlier, the boundary of the reserve was more than 10 km away from Dhekuli. When ctr was expanded in 1991, the boundary was stretched to the edge of several villages. In some cases, villages came inside the reserve. "These villages are (now) located on a very crucial corridor of migration of the animals from the Rajaji National Park side to the eastern side of Kosi," says R C Gautam, director of ctr .

In the government records, Sunderkhal is not a village but an 'encroachment'. The villagers are not entitled to the benefits from rural development schemes of the government. On the other hand, there are several tourist resorts not very far from the village which are 'legal'. But whenever the question of human-animal conflict arises, the blame invariably falls on these villages.

The ctr authorities have now started giving compensation for damages inflicted by animals to humans, cattle and crops in these villages. Bhawani Ram's family received an immediate relief of Rs 3,000 and were promised Rs 50,000. A compensation of Rs 2,300 is offered for every cattlehead lost to animals from the reserve. There is also a rate of compensation for crop losses, but the villagers are highly dissatisfied with it. But no compensation is offered for mango trees destroyed by animals. "If destroyed, we can get back rice or wheat in six months. But with the destruction of the mango trees, fifteen years of toil is lost," says Bharat Nandan Chimwal of Dhekuli.

To reduce human-animal conflict, a 14-km-long wall will be built along the southern border of ctr . But the wall, which will cost Rs 4.5 crore, is not a very sound idea, feels a senior forest official. It can easily be run over by elephants, he explains.

Meanwhile, with the only bread-winner dead, Bhawani Ram's family anxiously awaits the compensation. It could be a long wait.