As clean as coal

As clean as coal

will India let coal come clean? The question has been begging for an answer for almost a decade, even though India was one of the first developing countries in the world to try its hands on clean coal technologies.

World over, the growing environmental concerns and the need to improve conversion efficiency levels have forced a number of electricity producers and governments to look for means to cut the noxious gases belching out from giant chimneys in the backyards of coal-fired power plants. The consensus was that the cleaner the input (coal), the lesser the emissions. Among the most popular clean coal technologies looked at were fluidised bed combustion, pressurised fluidised bed combustion combined cycle, and integrated gasification combined cycle (igcc).

India, through its state-owned engineering monolith Bharat Heavy Electrical Limited (bhel), commenced a programme to harness igcc technology way back in 1989. One reason why bhel opted for igcc was that it was most suited for Indian coal feedstock, in which the ash content is as high as 42 to 43 per cent. Coal-based thermal power stations account for about 70 per cent of the power generated in the country.

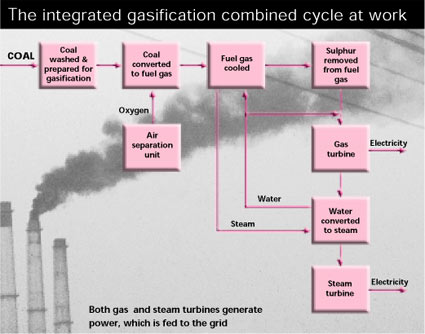

igcc technology is based on a process called coal gasification in which solid coal is converted into a synthetic gas composed mainly of carbon monoxide and hydrogen. Besides, it uses both gas turbines and steam turbines side by side to squeeze out maximum power. Sulphur in coal, the burning of which is responsible for sulphur dioxide emissions, is taken out of the system much before it is fed into the combustion chamber. This is done by diluting the purified synthetic gas with nitrogen and saturating it with water. The clean gas that emerges from the gasifier is then used as fuel in a gas turbine. Air pollution from fly ash is too minimal as it is collected as bottom ash in the gasifier. Another advantage is that the turbine's exhaust contains carbon dioxide in a highly concentrated form, which makes it easier to capture and convert into something less damaging to the environment.

The 6.2 mw igcc plant, set up in 1989 at a cost of Rs 15 crore at bhel's Trichy unit, was the first coal-based igcc plant in Asia and the second in the whole world. Since then, a number of new igcc plants, with higher efficiencies and greater capacities, have come up in different industrialised countries.

According to Kalipada Basu, former general manager (energy systems) at bhel, Hyderabad, and currently adviser at the Centre for Energy Technology at Osmania University, igcc is the ideal technology for India as it will help utilise the country's abundant quantities of low grade coal without much serious health and environmental implications. He wonders why, even after bhel has demonstrated the capability to scale up the technology to 100 mw, the Government has not come forward to support the technology.

It is said that with current designs, igcc plants are capable of operating at an efficiency of 45 per cent or higher, compared to around 35 per cent for conventional generation systems. This efficiency rate may be two to three per cent less than natural gas-based combined combustion technologies. But, Basu says, "What is more important is that it allows us to make use of our own coal feedstock.'

It's worth considering that India's current natural gas production may be enough to meet its current demands. But, with more and more natural gas-based power stations coming up it may have to resort to imports in the near future. The natural gas-powered plants will then get economically less efficient.

igcc plants are 10-20 per cent costlier than conventional coal-fired stations. However, if one takes into consideration the health and opportunity cost, this will be more than comparable, says Basu.

Meanwhile, public sector National Thermal Power Corporation