Win some, lose some

Win some, lose some

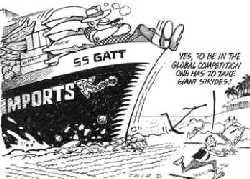

ON DECEMBER16, 1993, South Korean Prime Minister Hwang In-Sung resigned, taking responsibility for the opening up the country's rice market to imports. Soon, the entire cabinet followed suit. The impact of the Uruguay round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was not restricted to South Korea.

Farmers all over reacted angrily. However, the big farmers of the US and rice exporters of Thailand were thrilled at the market liberalisation. As news of the agreement made in Geneva was flashed across France, the country's powerful farming lobby started barricading highways and holding demonstrations against the pact (Down To Earth, January 15, 1994).

Handsome compensation The French government has offered its farmers handsome compensation for their loss of subsidised exports. However, now that the agreement has been approved, it is unlikely the government will make further concessions.

Japanese farmers, too, protested the decision to allow rice imports. Opposition parties from right to left accused Prime Minister Morihiro Hosokawa of treachery for allowing in heathen grain.

However, opinion polls suggest most of Japan, including the business community, now supports a liberalisation of the rice market. As disruptive as rice imports would be, most Japanese seem to accept that it would be even worse if Japan were to be held responsible for wrecking the GATT talks.

The government will, nevertheless, need to compensate farmers for the losses they will incur because of liberalisation, if it is not to be seen as selling out the farm sector to please the US and other foreign trade partners. Hosokawa had little to say on this beyond promising that he will set up an Emergency Agriculture and Farming Area Headquarters. This will try to work out new policies for the rationalisation of agriculture, a sector that has fallen far behind the rest of the economy in terms of costs and production. Chu Takeshi, a rice farmer in Tokyo, said the government's failure to work out a comprehensive farm policy was the biggest issue -- more important than rice import liberalisation.

In Seoul, South Korean president Kim Young Sam told his country he "had no choice but to seek competition and cooperation inside the GATT system rather than seek isolation in international society". The country's farmers do not see it quite that way. Kim's announcement incited stormy protests in a country where 85 per cent of the farmers grow rice and the small farm is seen as the bulwark of traditional values. Promises of government compensation may not go far in persuading them otherwise.

In Taiwan, Sun Ming-Hsien, chairperson of Taiwan's Council on Agriculture, expressed his opposition to rice imports, saying, "If we have to import rice, we can, and then...throw it away."

Caribbean banana exporting countries said the British market for the fruit could be adversely affected as a result of offers made by the EC in the Uruguay round. These entail increases of 100,000 tonnes in 1994 and 1995 in the tariff quota for import of the fruit from Latin America.

The accord doesn't go as far as Brazil expected. Says Luiz Felipe Palmeira Lampreia, the country's negotiator at the GATT talks, "There will be more subsidised exports (from developed countries) on the market for the next few years, and that will cost us jobs and exports."

And, many US family farm groups, who were supported by 60 senators, told President Bill Clinton of their opposition to the major elements of the Dunkel text, according to the Fair Trade Campaign of the US.

However, Wayne Boutwell, president of the National Council of Farmer Cooperatives of the US, which represents approximately 4,000 local cooperatives, says the agreement is "in balance pretty good" for US farmers. "This is a marked improvement" from current terms, he says. Another industrialist praised the accord, saying it "will bring about a big growth increase in trade that helps everybody". As European farm subsidies tend to be higher than those in the US, the cuts negotiated in Geneva will mean a bigger change for European agriculture.

The gift of GATT

Besides, farmers in Thailand -- the world's biggest rice exporter -- refer to GATT as a "gift", because it has forced previously protected rice markets to open up to imports. This is despite estimates by analysts that the share of such markets available to exporters will be small.

Experts temper this optimism, saying the GATT farm deal could lead to a 10 per cent rise in the prices of agricultural products, in spite of increases in production, because of the prohibition on dumping of subsidised food exports on world markets. They point out export subsidies by the US and the EC had depressed prices in recent years.