Neptune s sorrows

Neptune s sorrows

Losing colour

From central America to Austrelia, from the 2,000-km Great Barrier Ref to the small, reefs in Pacific islets, bleaching takes the life out of corals the world over

Corals, the rainforests of the oceans, are dying. Victims of global warming, scientists say 10 per cent of the Earth's coral reefs have been reduced to skeletons, another 30 per cent are in a critical condition and a further 30 are under severe environmental stress. "By the year 2050 they could all be dead,' says Clive Wilkinson of the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network ( gcrmn ), Townsville, Australia. "If the projected levels of climate change are not stopped, the doom may be just 30 years away,' warns the United Nations' Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change ( ipcc ).

The ipcc projects coral reefs to be among the most sensitive ecosystems to long-term climate change. They are small animals, mostly living in vast colonies, harvesting nourishment and energy from microscopic algae (plants called zooxanthellae), which inhabit their cells by the thousands. The algae are golden brown in colour and combine with other pigments to lend their coral hosts, which largely have transparent tissues, a spectacular hue. When environmentally-stressed, corals lose much of their algae. In this state, corals appear white and are referred to as "bleached'.

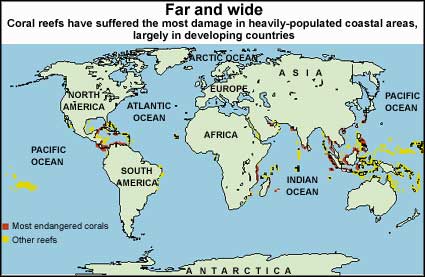

Coral bleaching was reported in at least 60 countries and island nations in 1998 (see map: Far and wide ). "Reports by experienced observers are of unprecedented bleaching in places as far apart as the West Asia, East Africa, the Indian Ocean, South, Southeast and East Asia, the far West and far East Pacific, the Caribbean's and the Atlantic Ocean,' says Wilkinson. Only the Central Pacific region seems to have been spared.

Preliminary assessments indicate that the Indian Ocean is the most severely impacted region. More than 70 per cent mortality has been observed off the coasts of Kenya, the Maldives, the Andamans and the Lakshwadweep islands. And about 75 per cent of the corals have been reported to be dead in the Seychelles Marine Park System and the Mafia Marine Plant off Tanzania, says Wilkinson.

The first report of coral bleaching came nearly 80 years ago. However, at that time Alfred Mayer, an oceanographer, dismissed it as a natural event because the events were localised, rare and the corals recovered soon after. It was only in the mid-1980s that coral reefs around the world began to experience large-scale bleaching frequently. However, the coral bleaching of 1998 is the most catastrophic and geographically extensive in recorded history, says Wilkinson. Moreover, unlike previous bleaching episodes, which were most severe at depths of 15 metres, the impact of the 1998 coral destruction extended to as much as 50 metres deep, he says.

Wilkinson points out four overlapping levels of bleaching:

- catastrophic: with massive mortality (often affecting near 95 per cent of shallow corals) in Bahrain, the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Singapore and in large areas of Tanzania;

- severe: with around 50-70 per cent mortality and with some coral recovery in Kenya, Seychelles, Japan, Thailand, Vietnam, and Belize;

- moderate and patchy: on some reefs in large areas, with a mix of coral recovery and around 20-50 per cent mortality but no ill-effects in other parts, such as in Oman, Madagascar, the inner Great Barrier Reef, parts of Indonesia and the Philippines, Taiwan, Palau, French Polynesia, the Galapagos, the Bahamas, Florida, the Cayman Islands, Bermuda, and Brazil;

- insignificant or no bleaching: in large areas of the world's reefs such as the Red Sea, the southern Indian Ocean, the Andaman Sea, most of Indonesia, large parts of the Great Barrier Reef, most of the central Pacific and parts of the southern and eastern Caribbean.

However, recent reports indicate that the Indian reefs, too, have not been left untouched. Bleaching has been reported in several areas along the reefs spread over Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Lakshwadweep, Gulf of Kutch and Gulf of Mannar. Corals that were abundant in the lagoons of the Lakshwadweep and Andaman and Nicobar Islands are getting destroyed (see box: Indian shores ).