THE FUTURE OF CLEAN ENERGY

THE FUTURE OF CLEAN ENERGY

W e can start this story like a science fiction thriller. But we want to talk reality. So, before discussing the hype that fuel cells generate, let us start on a rather elementary note. The dictionary will tell you that a cell is a unit in a device for converting chemical energy into electricity. Which is good. But there's a problem. The best of cells are useless after the chemical stops creating electricity. We are all familiar with the feeling - the dimming light of an electric torch that gives up the battle against darkness or the contorted, painfully stretched sound in a walkman that transforms music into cacophony in slow motion.

And then, warn the greens, is the environmental nuisance called battery acid. Disposal of used batteries is that darker shade of our 'green' conscience that we'd rather not be reminded of.If such moral pangs never prick you, nor the noxious fumes from automobiles and power plants, among scores of other things, stop reading this article. On the other hand, if you are interested in a future where cells don't have acid, cars don't belch smoke and the only byproduct of a power plant is pure water, read on. In the following pages, we intend to give you a peek into the real possibility of a future where a guilty conscience doesn't necessarily come gratis with consumer goods. It may seem too distant a future, but it is the only hope of ridding industrial development and modern consumerism of some of their negative connotations. It comes in fuel cells.

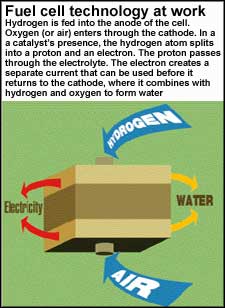

A fuel cell doesn't store chemical energy. Rather, it converts - through a chemical reaction - a fuel into electricity, squeezing out the juice without burning the fuel. So, as long as there is fuel, you have energy. And, if the fuel is pure hydrogen, then it reacts with oxygen to produce electricity, emitting only water and heat (see chart: Fuel cell technology at work ). In fact, astronauts aboard nasa's space shuttle drink water generated by on-board fuel cells. Fuel cells can also run on hydrocarbon fuels like methanol and petrol, but exhaust gases are emitted in such cells and they require a device called a reformer to extract hydrogen from the fuel.

But wait. Haven't fuel cells have been around for more than 100 years? Hardly anything's happened (see box: The history of fuel cells). The greens have been harping on their importance for the past 30 years, but fuel cells have failed to become a real alternative to polluting fossil fuels. Then why all the hype? Why this story?

We have good reason. Take the example of Ballard Power Systems Inc of Canada, which is the world leader in manufacturing proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Paul Lancaster, vice-president of Ballard in Burnaby, British Columbia, says, "Commercial fuel cells have always been seen as on the fringe - decades away. Now people recognise they are close to entering the market." How can he say that? Well, the way Ballard's share prices have been surging in the New York stock exchange is proof enough. Several automakers, working with companies like Ballard, intend to commercialise their fuel cell vehicles by 2004-2005 in North America and Europe.

If even this doesn't sound like a good enough indication, consider the remarks made by Sheikh Ramani, former Saudi oil minister, to The Sunday Telegraph of London. "Thirty years from now there will be a huge amount of oil - and no buyers. Oil will be left in the ground. The Stone Age did not come to an end because the world ran out of stones, and the oil age will not come to an end because we run out of oil." He predicts that fuel cell technology will have a dramatic impact on oil prices. Don Huberts, head of Shell Hydrogen, a new division of the oil giant Royal Dutch/Shell, agrees.

Fuel cells mean much more now than ever before because it isn't just environmentalists who are pushing for them. The corporates are coming in by the tens, saying 'let's talk business'. In its May 8 issue, the Business Week quotes industry analysts to say that if fuel cell progress continues at its present clip, the last car engine factory might close around the middle of this century. Amen.