A Sunrise industry

A Sunrise industry

Five years ago, Ama Herbal, a Lucknow-based company, quick to see potential in the natural dye industry, started to manufacture natural dyes. “The response was tremendous. Everyone asked us for samples within 15 days of writing to them,” says Y A Shah, the company’s managing director. “But later, everything backfired. There was no business in real terms. Whatever business we receive is from people involved in export or the local carpet industry,” he adds.

This about sums up the state of the natural dyes industry today. With the ban on certain azo dyes, there is an international demand for vegetable dyes. Strangely, domestic demand for natural dyes is yet to pick up. The absence of large-scale strategic cultivation of dye yielding plants does not ensure supply of raw material, which makes it difficult to manufacture large quantities of natural dye.

Says Kusum G Tiwari, of Mura Collective, New Delhi , an export company of naturally dyed textiles and clothes, “Getting an export order is easy, but executing it is a problem as it is difficult to get the dyes. Reproducibility of the same colour on a number of clothes is an ordeal,” she explains.”

Agrees G C Tripathi, managing director of Unique Dyers, a company involved in natural dyeing and export of carpets. “I have worked with natural dyes for the last 10 years and the major problem is shade consistency. A buyer will not accept four flowers in four different shades on four corners of the same carpet. We cannot execute bigger orders if there is no guarantee of colour,” he says.

But technology can come to the rescue. Gulrajani agrees that large scale production, necessary to meet hefty export orders, is not possible through the traditional method of processing vegetable dyes. “With super critical extraction carbon dioxide technology and computer matching, one can produce high quality pure dyes of the same shades. But you cannot invest much if you do not have big orders,” he explains.

But even with big orders, availability of raw material poses a basic problem. “A delicate balance needs to be maintained between demand and supply as trees cannot be grown overnight. Most natural dyers traditionally use local resources that grow wild. Therefore more land needs to brought under cultivation of dye yielding plants,” comments Kapila Himani, secretary of the Society for Indian Natural Dyers in New Delhi.

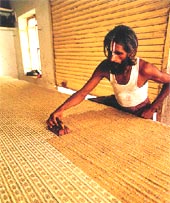

However, the impact of such findings is still to percolate down to the villages. Most dyers and weavers are in the small-scale industry and stick to traditional methods of dye extraction and processing (see box: Design tradition) . “We still use traditional dyes in the same way, as our forefathers,” says Derawala. “We prepare the black colour from jaggery (gur) and iron. The green or hara dhania colour is made from indigo, turmeric and pomegranate rind. We feel totally isolated. We need more information about raw material sources for different colours. We need to improve the fastness of natural colours and increase their acceptance in clothes. But who do we turn to?” he asks. Villages like Bagru, involved with natural colours are on their own. “The village receives no help from the government or any other institution,” complains Derawala. Natural dyers are reluctant to produce more dye as there is no market guarantee of local uptake. “Local consumers do not want natural dyes,”he comments.

He has hit the nail on the head. Natural dyes will continue to remain a sunrise sector unless domestic consumers wake up and demand naturally dyed textiles.

Customer is king

Pasha and her friends love to wear clothes dyed with vegetable colours. “The colours bleed during the initial washes. But washing the clothes separately is better than having chemicals next to your body,” asserts Pasha.

Obviously, not many people in India accept this. According to a study by the Uttar Pradesh Industrial Cooperative Society, (upico), Kanpur, growth in the use of natural dyes in India, was only felt in the carpet and woollen clothes sector followed by silk saris.

Domestic demand is stagnant. According to Farooqi, “Clothes dyed with natural colours are costlier by 25-35 per cent. Indians cannot afford it but Europeans can. Therefore, natural dyes are not going to take the country by storm, but the export market will surely grow. In the next five years, Europe and us will buy in a major way.”

Import of natural dyes by these countries has increased ever since the ban on certain azo dyes in 1996. In 1998, import demand for natural dyes in the us increased to $41 million, a hike of 70 per cent since 1994. The European import market also touched a high of us $70 million in 1998, an increase of 46 per cent from 1994. But, India’s share was a paltry export of us $6 million and us $ 5.5 million to us and Europe respectively (see table: Natural products).

“Commercialisation of natural dyes can be successful only with a systematic and scientific approach to extraction, purification and promotion of use of natural dyes,” Vankar said. In India, consumer demand is restricted by pricing, shade availability and colour fastness. “The need of the hour is certification from the government that our clothes are coloured with vegetable dyes,” suggests Prabha Nagarajan from Indigo India, a Chennai-based organisation.

Meanwhile, in cloth-dyeing centres like Sanganer in Rajasthan, or Tirpur in Tamil Nadu, natural dyeing would be on a limited scale with all products being meant for “100 per cent export.” We need to wake up to the call of nature.

| Natural products | ||

| Dye brand name | Plant source | Price (Rs. per kilogramme) |

| Alps Industries, Sahibabad | ||

| Basant | Mallotus philippensis | 371 |

| Caspian | Acacia nilotica | 625 |

| Nile | Indigofera tinctoria | 1,000 |

| Rhine-M | Kerria laccae | 1,600 |

| Ama Herbal, Lucknow | ||

| Mallow | Punica granatum | 500 |

| Madder | Rubia cordifolia | 1,500 |

| Bee | Acacia catechu | 300 |

| Insect | Rheum embodi | 850 |