Fading colours

Fading colours

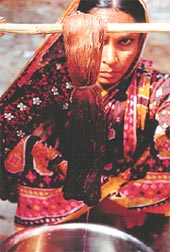

The Bandi river in Rajasthan is dying. Flowing through various villages of Rohet tehsil in Pali district, its water has a reddish hue like red rum. It can no longer be used for irrigation or drinking. "Even animals do not drink this water,' says Gangadhan Charan, a resident of Gadhawara village. The area is known for its small scale textile industry, which mainly uses chemical dyes.

Not far, in the metropolitan city of Delhi, Pasha is a lively, young working woman. Like her friends, she wears cool, trendy clothes and favours a couple of retail outlets, known for their naturally dyed handloom garments. "I do not want chemicals against my skin. If I can use natural colours for celebrating Holi, why not in my clothes?' she asks.

Surprisingly, while a few people in cities are moving towards natural, villagers are straying away from tradition in their sartorial preference. "Clothes dyed with chemical colours became popular as they promised a low price and colour fastness,' informs Ram Kishore Derawala, owner of a traditional dyeing and printing workshop in Bagru village. Derawala supplies clothes and dress materials dyed with natural colours to the handloom outlet that Pasha and her friends frequent.

"Our market has shifted from villages to cities as people from towns and cities like our clothes,' he adds. Derawala, who has been in the traditional dyeing business for decades, believes that natural colours are the future.

Dye-ing wisdom?

Natural dyes are colourants, with application in textile, paper printing inks, food, drugs, cosmetics and paint industries. Small quantities of these dyes are used for colouring leather, shoe polish, wood, cane and candles. However, in India the textile industry alone consumes nearly 80 per cent of natural and synthetic dyes.

Natural dyes, mainly used on textiles, are extracted from plants, animals and minerals. Also known as vegetable dyes, these are made from various plant roots, leaves, tree bark, flowers and fruit rind. The rind of pomegranate yields a golden yellow colour, indigo leaves are used to obtain a deep Prussian blue. "There are nearly 500 plant species in India that yield colour,' informs M L Gulrajani, professor in the department of textile technology at the Indian Institute of Technology (iit), New Delhi. Even animal residues like the secretions of insects like the cochineal, kermes and Kerria lucca or lac insect or the urine of a cow are commonly used in natural dyes.

Interestingly, earliest evidence of the use of natural dyes dates back to more than 5000 years old with madder (Rubia cordifolia) dye cloth found in the Indus river valley at Mohenjodaro (see box: Mad about madder). "But dyes may be older still, as few examples of early textiles have survived in India due to climate and burial customs,' says V P Kapoor of National Botanical Research Institute (nbri), Lucknow. Ancient Indians knew about mordants or addition of metallic salts that increased dye fastness and textile trade flourished.

India's supremacy in natural dyes was challenged in 1856 with the manufacture of the first synthetic dye stuff